Already within the first few weeks of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, it became clear how crucial the decentralization reform had become for the country’s resilience. Thanks to the redistribution of responsibility to the local level, the Russian plan to seize power in Ukraine failed. Resistance, organized locally by a strong civil society, demonstrated how deeply committed and successful Ukrainians are in fighting for their country’s freedom. Cities once again became fortresses, as they were in the past, and ordinary civilians became warriors. A wave of admiration swept across the world: “Be brave like a Ukrainian,” “Fight like a Ukrainian,” “Ukrainians are champions of resilience” — this is what we could hear in the media, at conferences, in the press, and in speeches by world leaders. The unity and resilience of Ukrainian civil society motivated the world to support Ukraine in its fight against the imperialist aggressor. Ukrainian cities, as part of autonomous hromadas, played a decisive role in defense and demonstrated a remarkable degree of social resilience, which is one of the aspects of “urban resilience.” But what truly makes cities resilient? Anna Kuzyshyn, urban planner and architect, researcher at the Department of Urban Planning at the Rheinland-Pfalz Technical University of Kaiserslautern-Landau (RPTU), Germany, reflects on this.

With this article, we are launching a special project on resilient cities in Europe and around the world. In future publications, we will explore the most interesting examples of urban resilience concepts, analyze their effectiveness, and try to identify ideas that may be useful for Ukrainian cities.

What Is Urban Resilience?

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development was adopted by all UN member states in 2015. It includes 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) covering a wide range of issues — from combating poverty to protecting the environment. One of the key themes is the development of cities as centers of economic activity and innovation, which require balanced planning and effective governance.

At the European level, these global goals were specified in the Leipzig Charter (2007) and the New Leipzig Charter (2020). Both documents emphasize the importance of sustainable urban development with active participation of citizens in decision-making, multilevel governance, and an integrated approach that combines social, economic, and environmental aspects of city development. These principles support the creation of more sustainable, inclusive, and vibrant urban environments across Europe.

At the European level, these global goals were specified in the Leipzig Charter (2007) and the New Leipzig Charter (2020). Both documents emphasize the importance of sustainable urban development with active participation of citizens in decision-making, multilevel governance, and an integrated approach that combines social, economic, and environmental aspects of city development. These principles support the creation of more sustainable, inclusive, and vibrant urban environments across Europe.

Although the term urban resilience appeared in the European context as early as the beginning of the 2000s, in the New Leipzig Charter of 2020 it is mentioned only in the context of resilience to climate change and economic processes, without addressing challenges related to the COVID-19 pandemic and military actions in Europe, particularly in Ukraine.

Although the term urban resilience appeared in the European context as early as the beginning of the 2000s, in the New Leipzig Charter of 2020 it is mentioned only in the context of resilience to climate change and economic processes, without addressing challenges related to the COVID-19 pandemic and military actions in Europe, particularly in Ukraine.

It is worth noting that in Ukrainian urban studies, the term resilience (Lat. resilire — to bounce back, return to a previous state) was not widely introduced and was translated into Ukrainian as “стійкість” (stiykist, stability or steadfastness). This caused some misunderstanding of the term’s meaning, as stiykist and resilience are not exact synonyms. Stiykist is often associated with nezlamnist (unbreakability or perseverance), especially in wartime conditions, but in fact, urban resilience also includes adaptability and transformation. It implies a city’s ability to cope with various threats and shocks, such as climate change, natural or man-made disasters.

There is often confusion between the Ukrainian concepts of stalist (sustainability) and stiykist (resilience) due to their similar sound and, at the same time, insufficient clarity for the general public. It is important to understand that resilience is merely a condition for achieving sustainability. This is confirmed by the definition of urban resilience by UN-Habitat as “the measurable ability of any urban system, with its inhabitants, to maintain continuity through all shocks and stresses, while positively adapting and transforming toward sustainability.”

In other words, a city must analyze potential risks, develop response strategies, and act proactively to prepare for threats, whether natural or anthropogenic, sudden or accumulating, expected or unforeseen. This not only helps to protect human lives and ensure the uninterrupted operation of critical infrastructure, but also to preserve historical and cultural heritage, support sustainable development, and foster an urban environment that is attractive for investment.

Key Principles of Urban Resilience

According to UN-Habitat, urban resilience is based on five core principles:

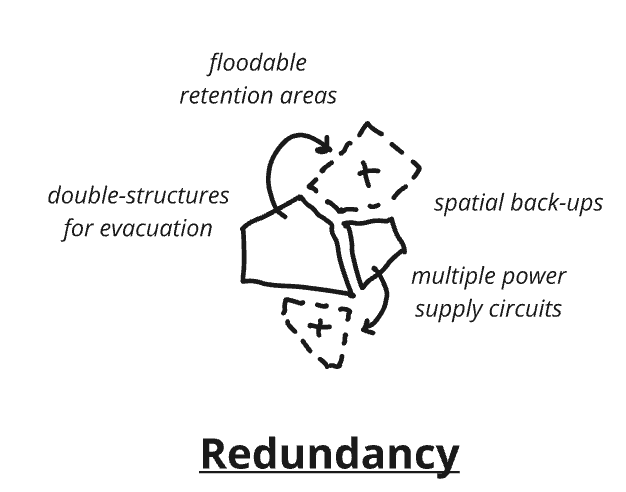

Redundancy

The duplication of key functions in a city provides backup capacity (space and infrastructure), enabling rapid response to unforeseen risks and ensuring access to essential infrastructure when needed. For example, having multiple sources of drinking water guarantees uninterrupted water supply in the event of a failure of one of them, while designated areas for flooding and water overflow help effectively manage river floods and heavy rainfall, minimizing the impact on the city.

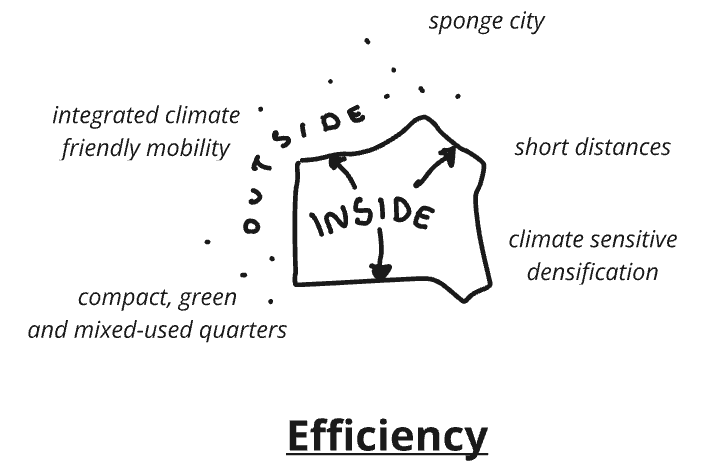

Efficiency

Urban environment functions are designed with space efficiency in mind and are integrated into existing structures, contributing to the development of effective and flexible spatial solutions. For example, compact and multifunctional planning of urban districts or systems for rainwater collection and wastewater recycling that support the optimization of water resources.

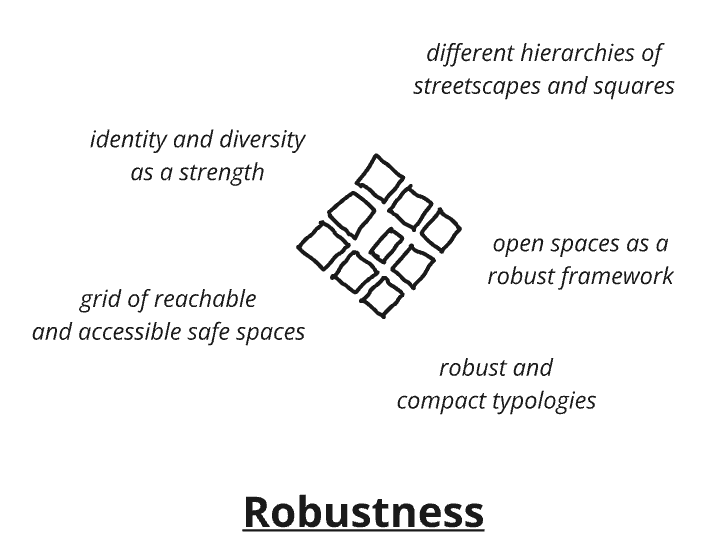

Robustness

Robust systems incorporate precautionary measures, remain self-sufficient in emergencies, and are capable of overcoming crises independently. For example, a city recognizes and preserves its identity, its structure is based on reliable and compact typologies, and its network of accessible safe spaces — parks, squares, streets, and open areas — serves as a strong framework.

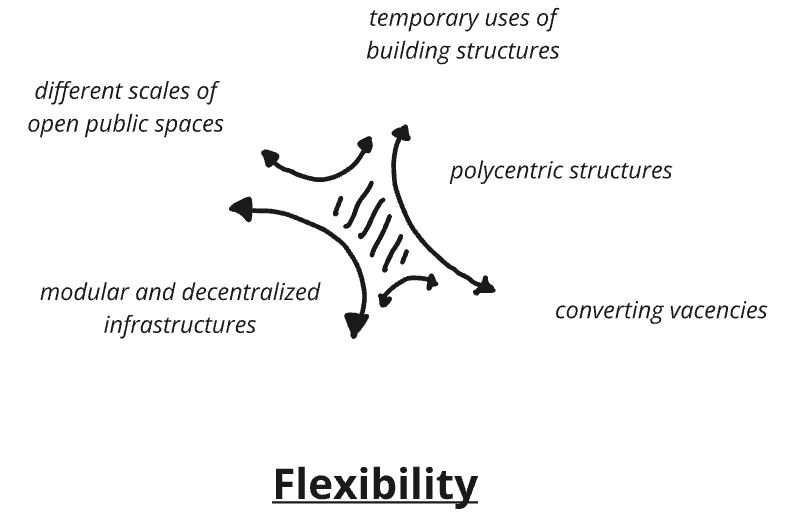

Flexibility

Flexible systems can change, evolve, and adapt to shifting circumstances. For example, during disasters, a city can quickly convert schools and community centers into emergency shelters and medical facilities to accommodate those affected.

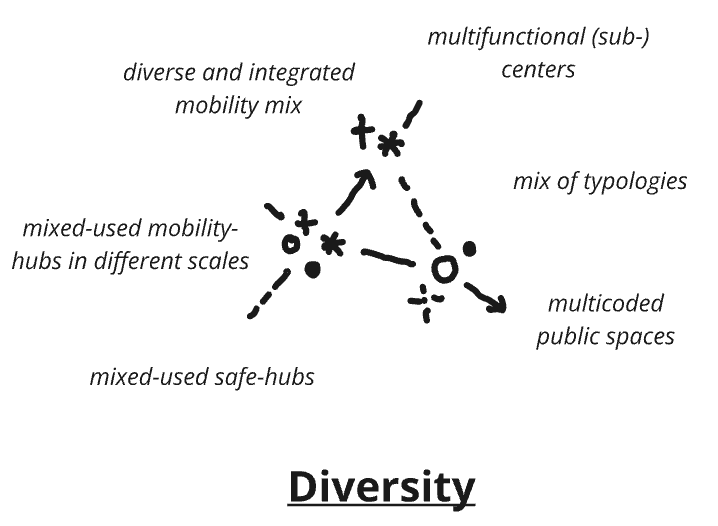

Diversity

Urban systems are less vulnerable to disruptions when there are various alternatives and options to choose from. Diversity allows for quicker crisis response and better adaptation to new conditions. Examples include mobility hubs with different modes of transportation, multi-coded public spaces, multifunctional safe hubs, and more.

Types of Urban Resilience

Urban resilience can be reactive, when a city takes action during disasters — such as floods — to save lives and property; proactive, when a city prepares for a possible flood by building additional drainage structures and implementing, for example, the “sponge city” concept; and reflexive, when previously implemented measures to prevent disasters are monitored and improved, and new models are developed for overcoming potential crises and their consequences.

Reactive resilience is defined by the ability to respond quickly to a disaster, stabilize the situation, and save lives and property. This is the first stage of crisis management, which includes the rapid deployment of emergency services and the coordination of their work. The main actors are rescue and fire services, which carry out search and rescue operations, extinguish fires, clear debris, and ensure evacuation. Medical services provide first aid to the injured, organize transportation to hospitals, and set up field hospitals. Utility departments are responsible for restoring critical infrastructure, including power and water supply, heating networks, and road infrastructure. Police and the National Guard maintain public order, oversee evacuations, and prevent looting. The local government also plays an important role by coordinating the work of services, providing resources, and informing the public. Key measures include emergency alerts, evacuation of people, medical assistance to victims, elimination of disaster consequences, and removal of threats. Temporary provision of vital needs includes the deployment of aid centers, supplying people with food, water, and temporary shelter.

Proactive resilience focuses on risk management, predicting potential threats, and assessing vulnerable areas in the city, which allows for minimizing the consequences of possible disasters. The main objective is to identify weaknesses in urban infrastructure and develop strategies to reinforce them, as well as to create effective protection mechanisms for residents. Particular attention should be given to vulnerable population groups, including elderly people, children and infants, people with limited mobility, and individuals or families with low income. These categories have limited resources and capabilities to cope with crises on their own, which is why their support and protection are a priority in planning proactive resilience measures.

An important aspect of proactive resilience is the analysis of vulnerable infrastructure, which includes facilities critical to urban life. These facilities include hospitals, kindergartens, schools, nursing homes, women’s shelters, and centers for internally displaced persons (IDPs). They require additional safety measures and improved resilience to potential threats.

Special attention should be given to critical and military infrastructure that ensures the vital functions of a city. This includes energy facilities, drinking water supply systems, food reserves, information technology and telecommunications, transportation networks, road infrastructure, waste processing plants, as well as government and administrative buildings. In the Ukrainian context, military facilities are additional serious factors that require particular attention.

At this stage, key measures include developing urban resilience concepts based on the types of threats that a particular city may potentially face. Examples of policy documents focused on climate change adaptation include the Resilient Rotterdam Strategy, the Freiburg Climate Change Adaptation Concept, the Milan Air and Climate Plan, among others. In the context of disasters, one can refer to the Sendai case of a Disaster-Resilient and Environmentally-Friendly City and the experience of New Orleans. For Ukraine, in the context of war, particularly valuable examples may include the case of Helsinki and Rotterdam. The main actors in this case are urban planning and municipal departments, but with an integrated approach, they will be joined by previously mentioned emergency and fire services, medics, police, and the military.

Reflexive urban resilience involves monitoring the effectiveness of already implemented concepts and measures. This stage is particularly complex, as it requires thorough analysis over months and years, especially during new disasters and challenges. Key actions include tracking the quality of implementation and application of measures for improving urban resilience, working to correct mistakes and developing new iterations of concepts, improving the qualifications of actors, continuous self-learning and knowledge exchange. The primary actors remain urban planning and municipal departments, but educational institutions may also become involved to work on the monitoring process and train current and future actors.

***

Today, Ukrainian cities, in addition to the war, face the same challenges as most European cities: climate change, pandemics, and economic instability. However, the war adds a new dimension to these problems, complicating their resolution and creating new threats to urban infrastructure and community life.

Ukraine needs not only solutions for rebuilding destroyed cities, but also strategies for adapting to the realities of wartime, taking into account the uncertainty of its duration. What matters is not just recovery, but the creation of robust, flexible cities capable of responding to modern challenges and being comfortable for residents. The experience of other cities, not only European ones, can be a valuable source of knowledge for Ukraine. Studying global best practices will enable Ukrainian cities to respond more effectively to threats and adapt to new realities.

In future publications, we will discuss various approaches to improving urban resilience: to learn about climate change adaptation and flood mitigation, we will look at the cases of Rotterdam and Freiburg; in the context of natural disasters, we will examine the experience of the city of Sendai in Japan; and to explore resilience against military aggression, we will refer to the example of underground Helsinki.

This article series is the result of the educational seminar Learning from urban resilienсe international — transfer points for Ukraine within the framework of the DAAD project Ukraine digital: securing academic success in times of crisis, supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). The seminar was held in cooperation between the Rheinland-Pfalz Technical University of Kaiserslautern-Landau (RPTU) and the Kyiv National University of Construction and Architecture (KNUCA), with the participation of architecture, urban planning, and geography students from KNUCA, Kyiv National University, O.M. Beketov Kharkiv National University of Urban Economy, and Odesa State Academy of Civil Engineering and Architecture.

The course is curated by Liubov Apostolova-Sossa, PhD in Technical Sciences, Head of the Department of Urban Economy at the Faculty of Urban Studies and Spatial Planning of the Kyiv National University of Construction and Architecture; and Anna Kuzyshyn, urban planner and architect, researcher at the Department of Urban Planning at the Rheinland-Pfalz Technical University of Kaiserslautern-Landau (RPTU).

References

1. Agenda 2030. https://sdgs.un.org/goals

4. Resilient Cities Network. https://resilientcitiesnetwork.org/what-is-urban-resilience/

5. Rifkin, J., 2022: Das Zeitalter der Resilienz: Leben neu denken auf einer wilden Erde. Frankfurt, New York.

6. Dosch, F.; Einig, K.; Jakubowski, P.; Kawka, R.; Kurnol, J.; Rauch, C., 2022: Zeitenwende auch für die Raumordnung? Konsequenzen des Ukrainekrieges für die Raumentwicklungspolitik in Deutschland. Informationen zur Raumentwicklung (IzR) Heft 4/2022, 10–25

7. De Flander, K.; Hahne, U.; Kegler, H.; Lang, D.; Lucas, R.; Schneidewind, U.; Simon, K.-H.; Singer-Brodowski, M.; Wanner, M.; Wiek, A., 2014: Resilience and Real-life Laboratories as Key Concepts for Urban Transition Research / Resilienz und Reallabore als Schlüsselkonzepte urbaner Transformationsforschung. Zwölf Thesen. GAIA — Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society 23/3: 284–286.

8. Kaltenbrunner, R., 2013: Mobilisierung gesellschaftlicher Bewegungsenergien — Von der Nachhaltigkeit zur Resilienz — und retour? Informationen zur Raumentwicklung (IzR). Heft 4.2013: 287–295.

9. Kegler, H., 2021: Resilienz: Strategien & Perspektiven für die widerstandsfähige und lernende Stadt. Bauwelt Fundamente Band 151. Boston.

10. UN Habitat, o. J.: Resilience and Risk Reduction | UN-Habitat. https://unhabitat.org/topic/resilience-and-risk-reduction

11. Hafner, S.; Hehn, N.; Miosga, M., 2019: Resilienz und Landentwicklung. Vitalität und Anpassungsfähigkeit in ländlichen Kommunen stärken. München.

12. DAAD. https://www.daad.de/en/information-services-for-higher-education-institutions/further-information-on-daad-programmes/ukraine-digital/

13. KNUCA. https://www.knuba.edu.ua/faculties/fupp/kafedri/kafmg/staff/?utm

14. RPTU. https://ru.rptu.de/fgs/stadtplanung/team/anna-kuzyshyn-msc

Header photo: Unsplash / Marti Sesarino