Helsinki, the capital of Finland, is a city that hides an entire world beneath it. Like many other European capitals, it has experienced numerous historical upheavals and wars, but these very circumstances gave rise to the formation of a unique underground infrastructure. Today, Helsinki has one of the largest and most complex systems of underground structures in the world. It is not only a network of bomb shelters but also a space for everyday life — with gyms, shops, museums, and cultural centers. In total, there are about 50,500 civilian shelters functioning in Finland, capable of accommodating up to 4.8 million people. In Helsinki, the shelter coverage level is 134%, which is enough to protect not only all residents but also the city’s guests [1]. The underground space here is not just a means of protection but a response to the current challenges, combining safety with comfort and care for urban life.

From War to Peaceful Life

The history of underground Helsinki begins during the years of World War II. Between 1939 and 1944, the city endured several waves of Soviet bombings, and it was then that the construction of the first underground shelters, places where the civilian population could find protection from air raids. However, the real impetus for the development of underground infrastructure was provided by the Cold War. At that time, Finland found itself literally on the edge. On one hand, membership in Western structures; on the other, the necessity to maintain neighborly relations with the Soviet Union. In this tense atmosphere, the issue of security became a top priority. It was then that shelters began to be built with a potential nuclear threat in mind: with powerful ventilation systems, autonomous water supply, and air filtration systems. These structures became the foundation for the future expansion of the underground city [2].

Underground Construction: How It All Works

Since the 1960s, Helsinki has actively used underground construction to its advantage. As urban space becomes increasingly densely built, more and more functions are being moved underground. To ensure effective and consistent use of the underground base for key projects — such as transport infrastructure, engineering networks, and large commercial facilities — the city developed the Underground Master Plan of Helsinki [3].

No other city in the world has created an underground plan of such scale. It regulates the location, size, and compatibility of major underground spaces — including rock caverns and transport tunnels — as well as defines the functional purpose of existing underground facilities. The protection and preservation of these spaces in the long term is considered critically important for the city’s functioning and resilience.

Тут має бути галерея № 1

In addition, thanks to its geographical location on solid granite bedrock, Helsinki has natural advantages for underground construction [4]. The city government decided to fully utilize this resource to build reliable and durable structures underground. Underground construction in Helsinki is not just an engineering task, but a strategic stage in the city’s development.

To create underground tunnels and structures, methods of drilling, blasting, and even special tunnel boring machines are used, which allow for the construction of a lot of tunnels in a short time. One of the key aspects that makes underground construction in Helsinki so effective is the use of modern ventilation and sealing technologies, which make it possible to create safe and comfortable conditions for people. Underground structures have their own air purification systems, backup sources of electricity and water supply, which ensures their autonomy [4].

In addition, engineers use geothermal systems for heating and cooling underground facilities. This significantly reduces energy costs and also makes the underground spaces environmentally friendly. The use of heat pumps based on seawater allows not only to conserve energy but also to reduce carbon emissions into the atmosphere [5].

How Underground Spaces Change Urban Life

The underground tunnels of Helsinki have long expanded beyond their original purpose as shelters or technical structures. Today they have become an integral part of the city’s infrastructure and are actively used for transportation, commercial, and cultural purposes.

One example of the effective use of underground space is the Amos Rex museum, opened in 2018. Located under the Lasipalatsi Square, it combines modern architecture with a historical environment, maintaining functionality and openness to the public. The architectural bureau JKMM Architects designed the underground exhibition halls, covered by five concrete domes with round skylights. These domes form a wavy surface on the square, integrating the museum into the everyday life of the city and turning it into a public space [6].

Тут має бути галерея № 2

Most underground commercial spaces are concentrated in the central districts of Helsinki, Kamppi and Kluuvi. Among these spaces, a key role is played by large shopping malls such as Forum, one of the oldest in the country, as well as Kamppi Helsinki. Although their buildings mostly have above-ground floors (five levels), there are one to three floors located underground. These shopping malls are among the ten largest retail venues in the city: in 2021, they were visited by 6.9 and 16.9 million people, respectively [7].

Smaller commercial establishments are located in pedestrian tunnels and at their intersections and resemble shopping malls in terms of content: cafés, restaurants, clothing and electronics stores, supermarkets. Importantly, all these underground spaces are integrated with the transport infrastructure of the city center thanks to the network of pedestrian tunnels. For example, east of the Forum mall are the Central Railway Station and the underground ticket offices, connected to the Rautatientori metro station. About 500 meters to the west is the Kamppi Helsinki mall, beneath which are the Kamppi metro station and an underground intercity bus terminal. To the south, these facilities are connected to two large underground parking lots. The pedestrian tunnels have exits to main streets and tram stops, making the underground space of the city center an organic extension of its commercially active districts.

In addition to the Amos Rex art museum with its underground exhibition halls and public space, there are other public underground facilities in Helsinki. In particular, Musiikkitalo, the Helsinki Music Centre, two-thirds of which is located underground. In the northern part of the city, in the Töölö district, lies the famous Temppeliaukio Church, carved directly into the rock, as well as the Olympic Stadium complex. After the 2015–2020 reconstruction, more than 20,000 square meters of new underground sports areas appeared here [8].

These public spaces are not yet connected by pedestrian tunnels to the city center, although some are accessible via technical passages. In the future, the construction of a new metro line is planned [9]. Other public facilities, such as Arena Center Hakaniemi, the indoor playground Leikkiluola, or the Itäkeskus swimming pool, can be reached by metro.

Pedestrian tunnels perform the function of city streets in this system. There are information boards, public toilets, benches, trash bins, drinking fountains, and advertising billboards. To keep up the atmosphere, some sections of rock are left exposed or ornamental elements are added to the walls. During peak hours, the tunnels in the city center are used by 1,500 to 2,000 people per hour [10].

Such pedestrian tunnels not only improve mobility in the densely built-up center, reduce the load on surface transportation, but also make the city more resilient to weather conditions — for example, heavy snowfall or downpours.

Today, Helsinki’s underground infrastructure is not just a technical solution but a way of organizing urban life. It allows the city to develop not only outward but also downward, preserving valuable surface space for maintaining architectural appearance and the natural environment.

Combining Daily Routine and Civil Defense

The underground structures described above serve as publicly accessible civil defense shelters. They are marked with the international symbol, a blue triangle on an orange background, and their entrances can be easily found on the city’s website. Most of these shelters look like entrances to underground parking garages, which are used daily by city residents, and they can also be accessed through metro stations. In addition, the city has less common, separately located rock shelters — according to official data, there are about ten of them, mostly located outside the city center [11, 12]. Some of them also serve a cultural function — for example, the Civil Defense Museum (Väestönsuojelumuseo) and the Kultsa Theater (Teatteri Kultsa) operate in protected underground premises. The entrance to such shelters most often looks like massive double gates.

The complex system of engineering tunnels that crisscrosses the entire city is particularly noteworthy. They are not open to the public; however, according to the Underground Master Plan, they often connect civil protection structures with each other. Technical entrances to these tunnels can be found in various districts of Helsinki, and they are usually marked with the logos of the companies responsible for their maintenance.

Finnish legislation strictly regulates the construction of defense shelters. They must be provided in industrial and warehouse buildings with an area of over 1500 m², as well as in educational, medical, administrative, and residential facilities if their area exceeds 1200 m² [13]. When obtaining a construction permit, an evacuation and civil defense plan is developed and coordinated with local services. In some cases, developers may be permitted to forgo a shelter if there is a publicly accessible facility nearby with sufficient capacity; or, conversely, an increase in shelter size may be required if the building is located in a high-risk area [14]. In Finland, shelters of this type make up approximately 85% of the total number [15].

As for the interior arrangement, this information is not public. It is known that shelters must meet enhanced requirements for durability, ventilation, and water supply. Toilets and rooms for providing medical assistance are mandatory. The minimum service life of such facilities is 30 years [13, 14].

After the beginning of russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Finland intensified the renewal of its protective infrastructure. News reports increasingly feature materials about the modernization of shelters, improvement of their equipment, and adaptation to modern conditions [15–18]. This once again confirms that Helsinki’s underground space is not only a part of the urban landscape but also a key element of the country’s security system.

The Underground Helsinki as an Instrument for Climate Change Adaptation

Another interesting aspect of the development of underground Helsinki is climate change adaptation. In the context of global warming and rising sea levels, Helsinki actively uses underground spaces to create systems that can help the city effectively respond to environmental threats. Underground water intake systems, rainwater collection reservoirs, as well as geothermal installations to reduce energy consumption — all of these are part of the city’s environmental strategy.

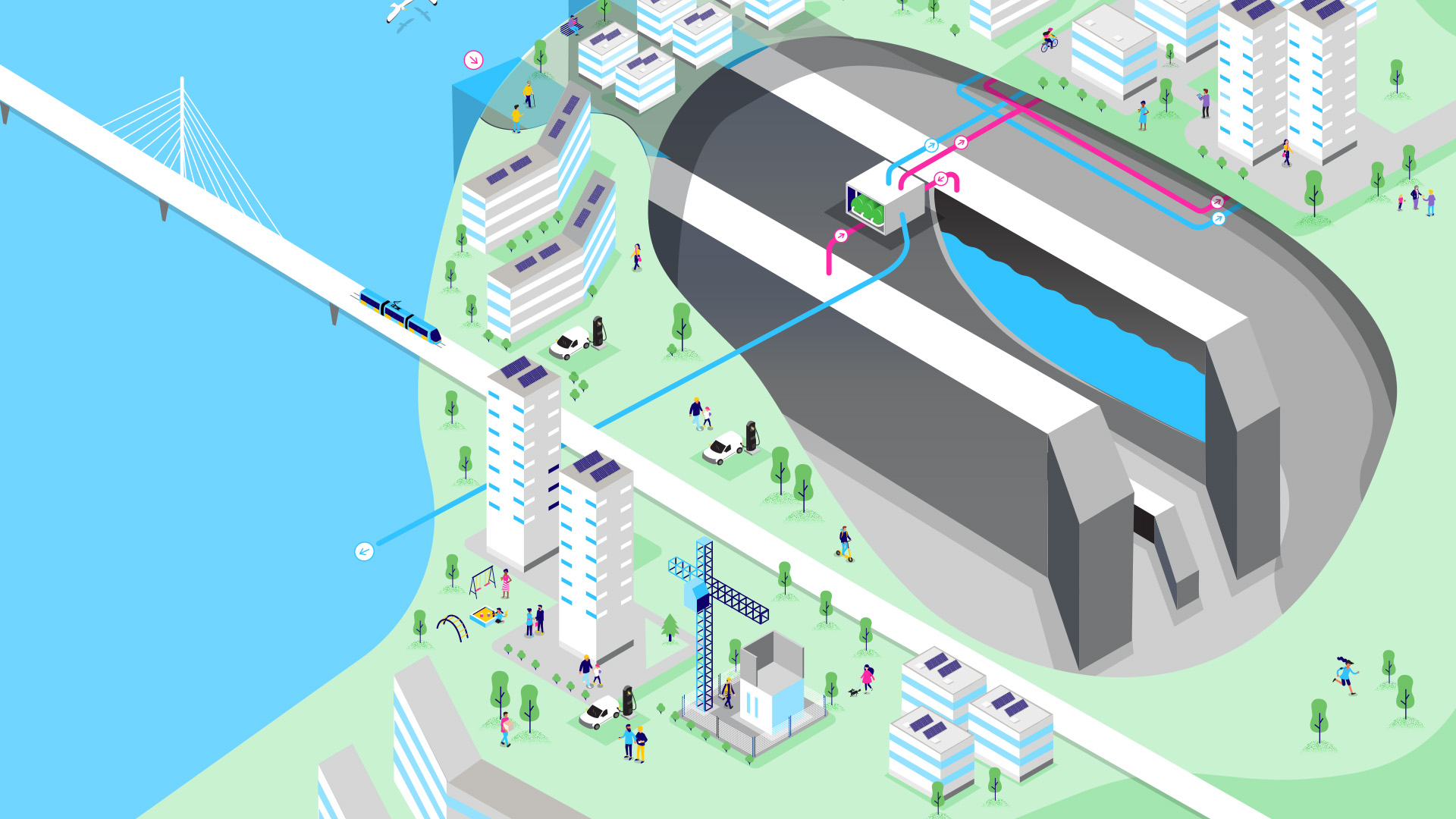

One example of such innovations is the construction of seasonal energy storage facilities in the Kruunuvuori caves, which were previously used as oil storage sites. Now, connected to the sea, they will play an important role in supplying energy to a new residential district. In summer, the caves will be filled with surface water heated by the sun, and in winter this water will be used as an energy source for heat pumps and heating. During the summer season, excess solar heat from buildings will also be collected and used for residents’ needs. Thanks to this energy storage, the new district will become practically carbon-neutral [19]. Similar solutions could also be adapted by Ukrainian cities on the coast or near large lakes.

Important utility networks are also stored in underground tunnels: from water supply to electrical cables. This helps reduce the risk of damage to these networks during natural disasters or technological accidents.

Underground Ukraine: How to Adapt Helsinki’s Experience for Safe Cities

The issue of civil defense in Ukraine has become critically important in cities located near the border with russia and under constant attack. Helsinki’s experience in using underground spaces is extremely valuable for cities like Kharkiv, where in May 2024 the concept of an underground town was presented. The project envisions the creation of a comprehensive infrastructure with safe public spaces, educational institutions, hospitals, commercial areas, and housing with a total area of 36,000 square meters [20]. As in the capital of Finland, this underground structure will be integrated with the metro, allowing urban activity to be maintained even under bombing.

A key advantage of such shelters is their multifunctionality: the metro serves for safe movement, public spaces provide social interaction, and commercial areas offer access to essential goods. Proper organization and integration of spaces play an important role. For example, in Helsinki, most entrances to the underground city are parking garage driveways, which are used in everyday life and are familiar. This facilitates quick access to shelters in case of an emergency. At the same time, it is important to remember that even with the presence of such multifunctional spaces, specialized shelters equipped with appropriate engineering systems and safety measures are necessary. The underground city is a complement to the protection system, not its replacement.

There is also the issue of regulating the use of such spaces during crisis situations. In particular, it is necessary to define the role of businesses: whether commercial establishments continue to operate or must partially or fully convert into publicly accessible shelters. This issue requires separate regulations and may be addressed individually in each city.

For settlements farther from active hostilities, Helsinki’s experience can serve as a model for the sustainable development of underground spaces. Many commercial facilities already use underground passages, but their potential remains underutilized. Planned integration of such facilities will contribute to the efficient use of space, particularly in central city areas and near metro stations. For example, part of the underground parking facilities could help reduce the load on surface areas, freeing them for other uses. The protection of critical infrastructure, including power grids, communications, and water supply systems, remains an important aspect. A possible solution could be the construction of technical tunnels, which are significantly more resistant to external threats.

Over time, the functions of underground spaces in cities may change. In particular, the underground schools in Kharkiv and Zaporizhia, which are opening now, can be transformed in peacetime into multipurpose spaces, from cultural centers to places for extracurricular education [21, 22]. Such premises are also suitable for housing 24-hour or noisy establishments, which would help minimize inconvenience for local residents.

The experience of other cities can also be useful for the further development of underground infrastructure in Ukraine. In Toronto, Canada, there is PATH, a 30-kilometer-long system of tunnels that covers commercial spaces with a total area of 343,700 sq. m and generates about 271 million dollars in taxes annually. A similar example is RÉSO in Montreal, which connects shopping, entertainment, and public spaces over a length of 32 km [23, 24]. Although these cities did not create underground infrastructure for safety reasons, their experience can be useful in matters of construction, adaptation to local conditions, and maintenance.

Finally, it is worth noting that Finland’s civil protection system has been developing for decades, since the 1950s, as it was one of the priorities of national security. What we see today is the result of systematic work, investment, cooperation between authorities and citizens, and constant adaptation to new threats. Ukraine will need years of persistent work, significant financial investment, and strategic planning to create an effective network of shelters, maintain them, and educate the population.

References

- Finland Has Civil Defence Shelters for About 4.8 Million People — Intermin.fi

- Kivimäki, V., & Vahtikari, T. (toim.). Eurooppalainen kaupunkikohtalo: Viipuri toisessa maailmansodassa — journal.fi

- Vähäaho, I. (2014). Underground space planning in Helsinki — researchgate.net

- Vähäaho, I. (2014). Underground space planning in Helsinki — researchgate.net

- Urban Underground Space Sustainable Property Development in Helsinki — Urban Environment Publications 2018:11

- Amos Rex — amosrex.fi

- Finnish Shopping Centers 2022 Kauppakeskukset — kauppakeskusyhdistys.fi

- Underground spaces to visit in Helsinki — hel.fi

- Metro Pasilasta eteenpäin — hel.fi

- Maanalainen kävely-ympäristö osana viihtyisää kaupunkia — hel.fi

- Kysymykset ja vastaukset väestönsuojelusta —pelastustoimi.fi

- Väestönsuojat — suomi.fi

- Väestönsuojan suunnitteluohje 2021 — pohjanmaanhyvinvointi.fi

- Valtioneuvoston asetus väestönsuojan laitteista ja varusteista 409/2011 — presto.fi

- Suomalainen väestönsuojelu alkoi kiinnostaa maailmalla — sen jälkeen Helsingin suojien korjaukseen tuli vauhtia — yle.fi

- Vallilan suuri pommisuoja remontoidaan 8 miljoonalla eurolla — helsinginuutiset.fi

- Helsingin kaupungin väestönsuojelusuunnitelma — ahjojulkaisu.hel.fi

- Helsinki kiirehtii useiden väestönsuojien kunnostamista — katso, kuinka lähellä asut — helsinginuutiset.fi

- Construction of seasonal energy storage facility in Kruunuvuori rock caverns kicks off — helen.fi

- Kharkiv representatives have presented a safe underground town project to potential investors in Luxembourg (Харків’яни представили потенційним інвесторам у Люксембурзі проєкт безпечного підземного містечка) — ukrinform.ua

- Here is what the first underground school in Ukraine looks like. It has been built in Kharkiv (Ось який вигляд має перша підземна школа в Україні. Її збудували в Харкові) — village.com.ua

- The second underground school opened in Kharkiv (У Харкові відкрили другу підземну школу) — suspilne.media

- PATH — Toronto’s Downtown Pedestrian Walkway — toronto.ca

- Toronto PATH Network — toronto.ca