Ukraine is preparing for a social housing reform, one of the key steps in fulfilling its commitments under the Ukraine Facility program, which is set to provide the country with €50 billion from the European Union by 2027. Following Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, the number of internally displaced persons has sharply increased, making the issue of social housing critically important. International partners support Ukraine in addressing this challenge, including the European Investment Bank (EIB), which funds relevant projects. Mistosite spoke with EIB Vice President Teresa Czerwińska, who oversees the bank’s operations in Ukraine, and senior urban development specialist Grzegorz Gajda about the challenges and possible solutions in the field of social housing.

What is the EIB’s activity in the housing sector now? What is it aimed at? What are the main priorities now? Who does the EIB cooperate with within the Ukrainian government?

Teresa Czerwinska: The EIB, as the bank of the European Union, plays a vital role in financing social and affordable housing projects across member states, supporting initiatives that enhance living conditions and promote social inclusion. The social housing sector in the EU is extensive, with tens of thousands of providers offering housing to approximately 100 million Europeans — equivalent to 20% of the EU population. Our mission is to provide financial support to this sector, ensuring access to quality housing for those in need.

Given the diversity of the sector and the varying needs across EU member states — and even within regions of the same country — the EIB tailors its financial solutions to meet the specific requirements of its borrowers. These borrowers include municipalities, public and private social housing providers, financial intermediaries, and private partners engaged in public-private partnerships (PPPs).

As the EU’s bank, our objectives align closely with the European Union’s broader goals, particularly in areas such as urban development, social and economic cohesion, and climate action. In practical terms, this means our financing supports well-located housing projects that cater to diverse populations, promote social inclusion, and ensure long-term affordability.

In Ukraine, the EIB has been actively collaborating with the Ministry for Development of Communities and Territories to support public social housing initiatives under the €200 million Ukraine Early Recovery Programme. This programme has enabled the rebuilding of 25 social housing subprojects to meet the needs of internally displaced persons (IDPs), particularly following the 2014 conflict. To date, seven of these subprojects have been successfully completed. Unfortunately, several social housing subprojects were located in conflict-affected areas and had to be halted due to the full-scale invasion in 2022. However, the allocated funds were reallocated to other subprojects in territories under Ukrainian control. Currently, several social housing developments are at various stages of construction in Poltava, Donetsk, and Zaporizhzhia Oblasts.

Moreover, a call for proposals under our Ukraine Recovery III Programme is now open until the end of January 2025. This initiative invites communities in Dnipropetrovsk, Kirovohrad, and Cherkasy Oblasts to submit applications for the construction, reconstruction, or major renovation of social housing facilities.

Looking ahead, the EIB is working closely with the Ukrainian government and the European Commission on two new social housing projects. The first focuses on the energy-efficient restoration of war-damaged apartment buildings, while the second aims to develop new social housing solutions. These initiatives are designed to both restore existing infrastructure and create new, sustainable housing options, ensuring long-term affordability and accessibility for those most in need.

What problems did the EIB face when it started financing social housing in Ukraine with the outbreak of the full-scale invasion?

Grzegorz Gajda: The challenges in financing social housing in Ukraine did not arise solely with the full-scale invasion but have deeper roots. Following the reforms of the ‘90s, Ukraine’s housing sector transitioned almost entirely from the public sector to the private one. And social housing is predominantly public housing or housing delivered for rent below market price by specialized, socially oriented entities.

As for dedicated social housing, there was no necessary institutional framework or eligible entities in Ukraine to borrow, nor were there sufficiently developed projects ready for financing. Moreover, there was no legislation defining eligible beneficiaries for social housing, the criteria for renting such housing, or the priority of access. There were no established laws defining the level of rents to be paid by the tenants and defining the legal, operational and financial framework for this type of housing and its providers.

Could you please tell us what problems good social housing could solve in Ukraine?

Grzegorz Gajda: When we look at the countries of Western Europe, which have well-developed social and affordable housing sectors, we can see that it helps address the following problems:

- Enables access to housing for young people who wish to leave their parents’ households and start new families;

- Attracts key workers, such as teachers, doctors, nurses, employees of public enterprises, involved in delivery of critical public services to population;

- Reduces the cost of housing overall, making it more affordable for everyone;

- Helps reduce commuting time, as housing with affordable pricing does not need to be built far away from the city centre. This is an important topic, as housing built far away from the city centre also means that in the future the city will have to build all necessary infrastructure for the people who live there. Such infrastructure, including schools, clinics, all kinds of utility services, and public transport solutions, creates a cost which is very high and will need to be covered by the city. We refer to this in economic terms as the external cost of suburbanisation.

How to make social housing financially sustainable and ensure that it will be able to cover its operating costs? Who should manage such housing?

Grzegorz Gajda: Actually this question addresses the key aspect which differentiates well-functioning public housing in Western Europe from what the citizens of Ukraine may remember from the Soviet era. In the Soviet Union, the providers of this type of housing, the Zheks, were not operating according to any economic principles. Their operation was mainly aimed at controlling the society rather than effective housing management. In contrast, in Western Europe, these providers are expected to cover their operating costs. They do not need to generate profits, but they must cover the expenses related to the operation and maintenance of the buildings they own. As a result, the operation of public housing does not create a burden on the cities’ budgets, and the buildings are well-maintained.

But this question is deeper. Best practice examples from countries such as France, Germany, the Netherlands — where we provide a significant portion of our housing-related financing — demonstrate that several interconnected elements contribute to the success and financial sustainability of the public housing sector:

- Housing is offered to a large and diverse group of people for rent, and this rent is diferentiated according to tenants’ income. This not only helps improve financial sustainability but also prevents segregation.

- There is a publicly sponsored financial intermediary institution which obtains its funds from private savings or capital markets and transforms them into very long-term loans (up to 25 to 50 years) used to build this type of housing. With this type of financing, its repayment will be possible with low rents paid by tenants without increasing public debt.

- Housing providers typically obtain buildable land for free and are not required to pay any dividend. They also very rarely sell the housing units they built in the past, as the revenue from renting the “old” units helps finance the construction of “new” ones.

Recently, the Deputy Minister of Community and Territory Development, Natalia Kozlovska, announced that a pilot project of social housing in 15 communities will soon be launched with the support of the EIB. What is the concept of this pilot, what model will such housing operate under, who can apply for it, what legislative acts will regulate such housing? Which communities will take part in it, what is the amount of funding?

Grzegorz Gajda: I can confirm that we have been approached by this Ministry and we are discussing this initiative. It is, however, still too early for us to provide specific details. Our aim is to do it based on European best practices. We also aim to use a financial mechanism that will include long term-loans from the European Investment Bank and grants from the European Union.

What model of social housing, particularly the financial and management aspect of it, does the EIB propose?

Grzegorz Gajda: At this stage of development, we would recommend Ukraine to consider a model of public housing companies owned by cities, organized as communal enterprises, which would offer housing for rent at affordable rates.

How will the social housing of this particular project fit into the framework of the bills that the government is currently working on, namely “On the Basic Principles of Housing Policy” and “On Social Housing”?

Grzegorz Gajda: The European Investment Bank was among the international financial institutions invited to provide comments to the law “On the Basic Principles of Housing Policy” at the stage of its drafting. Any housing project to be financed by the EIB will need to be developed in line with this law.

We have not been consulted regarding the law “On Social Housing”.

What is your overall assessment of the draft law “On the Basic Principles of Housing Policy”, the text of which is already publicly available?

Grzegorz Gajda: We reviewed the version of the draft law which was submitted to the Cabinet of Ministers for approval before it was submitted to the Parliament. Our assessment at that time was positive.

What best practices of housing policy could Ukraine adopt today? Please provide examples of other countries that, with the help of the EIB, independently have a system of sustainable social, affordable housing?

Grzegorz Gajda: The housing systems in various EU countries are very diverse, but there are some common principles that can be considered best practices. These include:

- The housing should be provided by socially oriented, non-profit organisations that aim to operate for a long time and constantly build and renovate their housing stock.

- The housing should be accessible to a widely defined group of people, with eligibility criteria covering 40% to 70% of the population.

- The focus should be on building a large stock of social and affordable housing, as economies of scale are of paramount importance here. Ideally, public housing should constitute at least 10–20% of the total housing stock.

- The role of the national government should be in regulation, data collection, analysis, policy setting, and in offering a centralized source of long-term funding. Delivery, however, should be at the local government level as much as possible, while maintaining the principle of adequate scale of operations.

- The rents paid by the tenants should be affordable and diversified, ensuring the financial sustainability of the housing providers.

- There should be significant involvement of society in decision-making related to social and affordable housing, and the decisions should be made in the most transparent way possible.

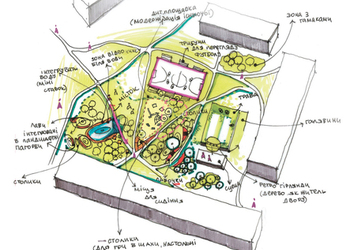

Тут має бути галерея № 1

Within the European Union, the countries where the EIB is most active are the countries of Western Europe, which already had well-developed social and affordable housing systems even before the EIB was established. Among other EU countries, I want to mention Poland as an example. For more than 10 years already, we have been financing the new modern public housing system in Poland, which, in our view, may be very relevant to Ukraine, with the addition that the process in Ukraine must be much quicker, given the acute housing needs.

Additionally, we have recently completed a Technical Assistance programme with one of the largest Central European cities. And at the moment, we have ongoing advisory programmes with Latvia and Czech Republic and many others in preparation.

We prepared this interview with the support of the Housing Initiative for Eastern Europe (IWO e.V.) and the German Federal Foreign Office (Auswärtiges Amt, AA).