In the previous two articles, we presented an argument that the currently proposed urban planning approach represented in the General Plan of Kyiv 2040 will be unable to resolve urgent problems of the capital and will in fact make certain problems worse.

Read the previous articles about General Plan 2040:

- Kyiv’s new General Plan has failed. What will come next?

- Kyiv’s General Plan is not an accident. Part II

We believe that Kyiv needs a renewed urban planning approach that can formulate an appropriate vision of the city’s future development while creating the political instruments that would allow the city to collectively arrive at this desired future. In this part, however, we will not propose a holistic urban planning strategy, since such strategies can only be created through open, inclusive, and comprehensive processes involving first local, then national, and then international collaborations and idea generation. Our focus, produced from an urban planner’s perspective, is instead on devising the fundamental and necessary visionary changes that we believe are needed in the GP process in order to «catalyse» new political, civic, and design approaches to planning in Kyiv. Both new methods and goals should shift away from those currently dominant in the contemporary neoliberal discourse, and from those inherited from the socialist-industrial era. We also acknowledge boldly that our suggestions to renew the current planning discourse and outcomes in Kyiv are guided by our values and professional backgrounds as practitioners and researchers with domestic and international experience.

New aims for planning in a pluralist era

The future of the city cannot be calculated. Many city components are impossible either to understand or to present with numbers, and attempts to reduce the complexity of the city to its so-called essential, quantitative components leads to costly mistakes. As we stated at the end of Part 2, such overquantification of planning leads to the sweeping of essential factors under the carpet, and to the exacerbation of subsequent problems like social alienation, natural habitat degradation, and heritage loss (Burckhard, 2019). Contrary to this situation, the aim of renewed planning should be to embrace the complexity of societal needs — in other words, to embrace the pluralism of the city — in the production of ideas for the city’s future. Given the perils of overquantified urban planning, is it any wonder that so many critiques of this planning model come from social sciences and arts? These include philosophy (Donald Schön); geography (David Harvey); history (Peter Hall); anthropology (Henry Lefevre); journalism (Jane Jacobs); sociology (Lucius Burckhard); music (Murray Schaefer), and architecture (Michael Southworth), just to name some of the main proponents. Arts and social sciences as a basis for planning open up new perspectives and instruments, necessary both for pre-planning phases and for generating new understandings of the city in planning processes.

What are some of these new understandings? Immaterial, qualitative values, such as city perceptions, interpersonal relationships, fresh air, acoustic horizons, city skylines, social equity, democratic involvement, human environment, historical landmarks, cultural diversity, city images, and memories are only a few of the city factors that cannot be understood through quantification. It is possible, however, for planners to be in a position to create and promote spatial and timeframe models to accommodate those needs (Huw Thomas, Values and Planning 2017).

New aims and priorities should include:

Intensive over extensive growth

- reduce the ecological footprint of citizens and businesses

- minimize destructive and unsustainable resource and land use

Basic human needs over consumption

- reserve and foster unrestricted access to natural and recreation zones, public spaces, clean water, air, and soil

Equal access instead of privileges

- foster equitable distribution of urban services such as education, public transport, cultural and medical facilities

Social- over market-driven development

- enable all citizens to rent, buy or build affordable housing with social infrastructure

Preservation over redevelopment

- protect urban history physically and develop public knowledge about it

- respect local community, traditions, and practices

An open instead of closed city

- respect the rights to collective and democratic governance of the city

- embrace inevitable yet highly unpredictable change with flexible planning.

Kyiv’s contemporary planning includes the unrealisable and undesirable aims desperately attempted during the last century — to overcome the «liveable chaos» of the city in favor of a tightly controlled order. Livable chaos is not negative; in fact, city existence depends upon it, because the city is dynamic, not fixed in place. Especially in Ukraine, urban planners, despite repeated calls for flexible physical planning, have never devised a model to do so besides the approach of adopting incremental and illegal modifications. And urban designers remain stubbornly fixed to nineteenth-century conventions of plan, section, and elevation for the dynamic model of the city. Diagramming a static future for what is a living being (the city) is akin to pinning a butterfly to a board and claiming that in doing so, one thereby understands a living butterfly. Only a few urban designers have ever conceptualized and embraced an understanding of the design of the city as a dynamic entity, and of devising planning and design solutions that embrace this dynamism rather than resisting it, in the manner of pinning a butterfly to a board.

Read more:

Degrowth for Human Prosperity

The planner must view the act of designing the city as one akin to the act of «painting on a river», as David Crane (1970) put it. Edmund Bacon (1980) promoted the planning of the city as a movement system, while Brent D. Ryan (2017) advocated for a «plural urbanism», permitting the collective shaping of the city by its numerous actors, yet in an intentional, aesthetically purposed way. Following this innovative thread of design practice, we propose a flexible or dynamic master plan as a new planning approach that achieves this aim.

Urban planning needs to become an integrated part of economic, political, cultural, and social development, as its detachment from the aspirations of citizens, scientists, artists, and entrepreneurs creates mistrust and absurdity. Priorities and strategies have to be based on the needs of the current and future generations to inhabit a liveable city without polluted air, water and soil. To achieve this desirable outcome, we now look into how spatial planning and urban development could change.

Change of principles and vocabulary

A clear statement of how planners should conduct themselves requires looking beyond professional ethics to the functions the profession serves, the tasks it is assigned. If a given task is harmful, executing it professionally is not desirable (Marcuse, 1975).

We suggest that different principles and language of planning are needed. These new principles would include polycentricity and horizontality; a sustainability imperative; and citizens as co-creators. These changes in the approach constitute our responses to the unsustainable; the disconnected nature of local spatial plans; the unrealistic, artificially calculated, and fixed-butterfly nature of static spatial plans, and these plans’ denial of the validity of public space as a forum for future civic action.

1. Focus on the process: Flexible, polycentric, and horizontal

The relation between formality and informality is typically based on formality’s exclusive priority. As a powerful meta-language, formality incorporates structures of power and domination and provides a prescriptive representation of the world mediated by norms, reference standards, and cultural codes (Planning for a Material World, Lieto & Beauregard 2015, p. 5).

Urban planning documentation must not be overestimated on its own. The process of its creation has to become even more significant. Current planners are obsessed with over-regulating, leading to gaps between the desired plan and real context. Often this is resolved by corrupted mechanisms and personal, uncoordinated decisions.

Flexibility is often called for, but its realization needs to become a new planning principle. While legal decisions certainly demand clear-cut rules, an effective spatial plan needs to be dynamic and flexible (Ryan, 2017). A flexible instrument such as a legal framework for urban land reallocation, vacancy reuse incentives, or temporary permits allows a plan to accommodate future changes and to remain integrated with other planning documents such as a strategic plan, a zoning and detailed plan, and others. Moreover, such a flexible instrument should provide an overlay of formal (zoning, detailed plan) and informal plans (community-led projects, for instance).

Communication and coordination between sectors and organizations have to become a principle. This can be provided by a polycentric and horizontal procedure of planning provision. Of course, planning must be guided by an integrated team of city administration and urban experts chosen on the basis of competition. City administration has to play a pivotal and proactive role in most of the development projects, securing and defending the public interest. Still, planning can no longer be produced solely by experts from state institutions. Local actors and businesses already strive to create guidelines and frameworks in parallel, and they must be taken into account if planning is to be coordinated and therefore democratic.

Representation and transparency of planning materials has to be a supporting condition of process-oriented planning. Documentation has to be created in a publicly accessible and understandable way that invites citizens, developers, independent experts, and civil society to participate. Moreover, planners need to be tolerant of postponing the planning document release if the open process demands it (Burckhardt, 2019). Lastly, there needs to be a decentralization of the local planning procedures to the level of district councils and administration, where local planning documentation can be publicly discussed, evaluated, and accepted on the terms of fair stakeholder participation by rayon (district) council members. Only then should the city council vote to update the land-use or general plan and legalize an urban project.

2. The sustainability imperative in planning: Reduce, reuse, recycle

Urban planning urgently needs to take very seriously the ecological balance and climate crisis as well as the low-carbon future of the city. This imperative can be translated to spatial and managerial instruments that aim to:

Reduce traveling distances, food miles, speculative construction, heat island effect, energy use and waste production. This means a search for methods and incentives to lessen the consumption of different goods and to change mobility patterns. It also implies the need to minimize waste creation at different stages of urban development, taking on the responsibility for evaluating and decreasing waste from the start of development.

Reuse abandoned or outdated structures, rooftops, food waste, agricultural areas, urban memories, and wastelands. A much more site-specific and less ambitious redevelopment on all scales, from zoning to a floor plan that drives the need to be creative and innovative in uncovering new potential users and uses. Within the GP, a new strategy for comprehensive revitalization needs to substitute the current «renovation», which is actually destruction, strategy for industrial areas.

Recycle sites of toxic industry, residential waste, private cars, fences, demolition debris, parking garages and highway interchanges. Take advantage of recycling to get rid of obsolete and damaging elements of the city, such as motorized personal mobility vehicles and redundant asphalt. Set new rules and priorities towards minimizing the remaining inefficient and unused areas with the aim of converting them to places of public interest with high sustainability criteria.

3. Citizens are co-creators, not consumers

Participation constitutes a facet of democracy in urban life, and it promotes the education of citizens as well as the promotion of negotiated and well-considered choices. And participation does even more than that, enabling urban dwellers to become co-creators. At the city scale, citizens can hardly assume the role of professionals, but on the level of local districts, streets and neighbourhoods citizens possess a much deeper understanding of the processes and sense of involvement due to their intimate knowledge of such areas (Jacobs, Habraken, Ryan). Formal and informal associations as well as NGOs are also of invaluable help to planners on the ground. To enable citizens’ right to participate, planning procedures have to provide a spatial and legal opportunity for active involvement by citizens throughout the process.

Read more:

Kyiv: interaction between local authorities and civil society

Permitting participation does not mean simply providing highly formalized procedures conducted by the city once every few years. Instead, participation means that a planning process should include all major steps in planning documentation. Planners’ and politicians’ fear of NIMBYism and speculative development is as much a failure of transparent communication of the common goals as it is a problem of poorly financed and conducted processes. Creating visibility of false participation processes can no longer suffice because people are frustrated by harmful planning decisions being made somewhere, without an opportunity for citizens to intervene and access the accurate planning information beforehand.

To create a valuable plan or regulation that will find public support in spite of a developer’s opposition is possible only via co-creation of a plan with the public and through publicity and transparency of plan regulations and concepts. A worldview in which citizens play only the role of consumers is far from the real-life urban processes that we observe. What was previously expected by powerful actors — the silent approval of the majority — is no longer a viable option. Many urban projects are meeting fierce local resistance, a sign of the growing and thriving civil society of Kyiv, and a welcome indicator that the «insurgent polis», with an active, engaged, and participatory citizenry is the reality of the city today. Planning needs to acknowledge, respect, and welcome this participatory reality, instead of pretending that it doesn’t exist for the sole benefit of developer groups and city administrators.

Making use of short and long-term opportunities

Whether or not power corrupts, the lack of power surely frustrates. Planners know this only too well. [...] A political process created not only a set of problems to be addressed, but the planner’s job as well. There is, therefore, no choice to be technical or to be political (Forester, 1982).

While we understand that any serious changes to the contemporary planning mindset and process existing in Kyiv may take an immense amount of time and energy, we propose that by building upon existing lines of action to strengthen the discontented voices and stimulate radically new solutions on the ground, such a shift in the contemporary mindset may occur without undue effort. Below are some of our suggestions.

Short-term, small-scale projects respond in a modest way to tackle the vast challenges of changing planning paradigms. Many local plans and conceptions are simply neglected instead of being applied for the benefit of the communities, and as such are almost never taken into account by municipalities in Ukraine. Small-scale and short-term projects help us move toward a desirable future, help us to achieve the suggested result of plans, as well as to reflect on the aim and principles of a new planning paradigm without taking difficult big steps all at once. It is easier with short-term and small scale to experiment and to make radical decisions that would otherwise be unavailable in political gridlock and business-as-usual approach that is typical of big-scale plans. A helpful step to achieve desirable outcomes is to designate short-term projects as equal in importance to strategic and long-term projects.

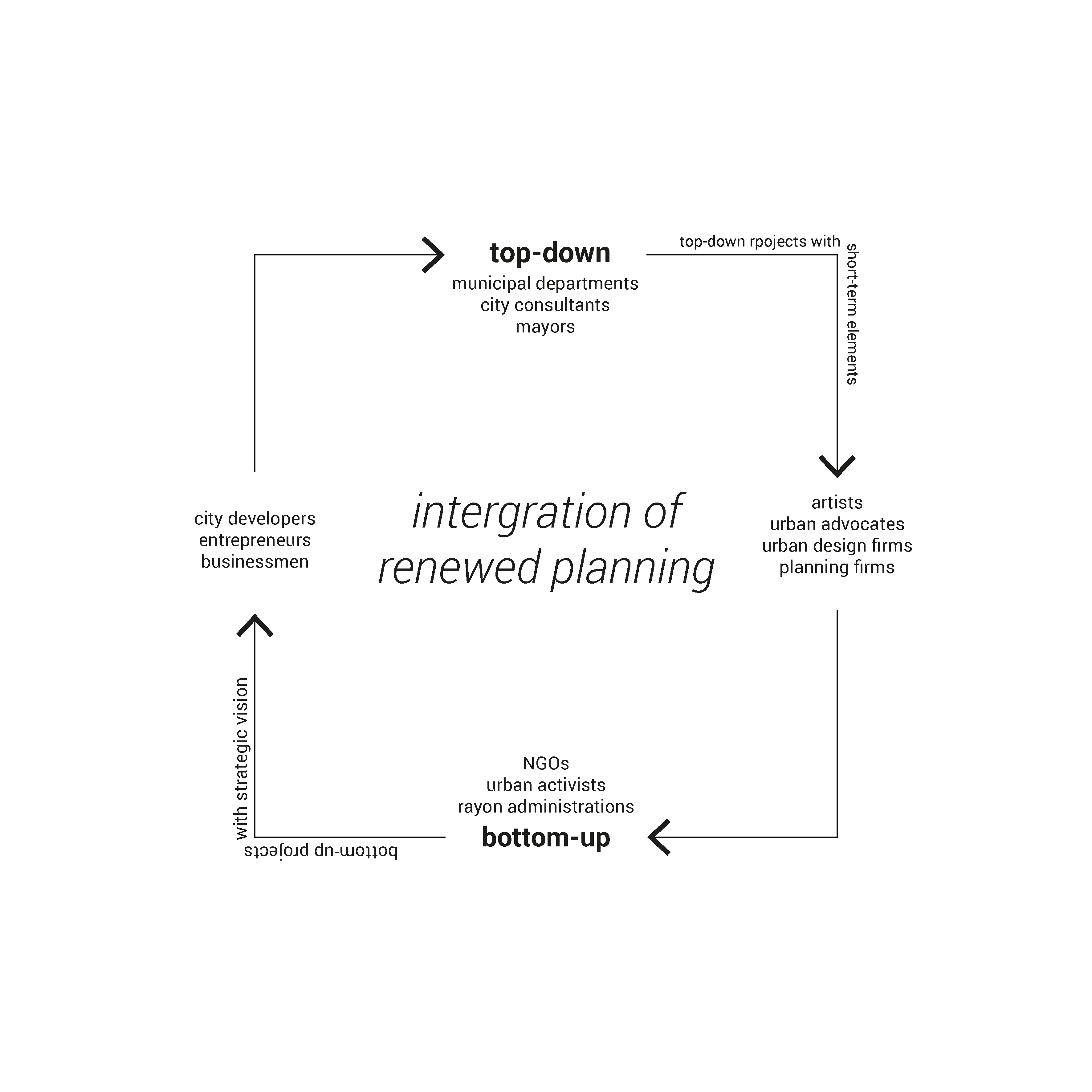

We are opposed to the «image» of a short-term project being a parallel field of action or activity that is detached from «formal» or «real» planning (Michel de Certeau). Instead, we suggest considering an integrated approach, in which the bottom-up has to learn how to be more long-term, and vice versa (Mike Lydon, Daniel Campo). Their presumed lack of formality is actually a strong side of these projects, as they obtain their persuasive power through negotiation, not coercion. In small-scale, short-term projects, both private and non-governmental ideas can become powerful tools fostering progressive development. But these will not suffice on their own.

Long-term projects should be initiated within a more research-oriented rather than a policy-making outlook. Engaging interested parties in a discussion often does not lead to any precluded result, but instead opens a horizon of options and strengthens the position of municipal administration, planners, and experts. Advancing methods of research are critical to assess and respond to contemporary challenges. The most important point here is to link planning to other related topics, such as social cohesion programs, ecological regulation, public space management, mobility planning, and others. Many of these topics are being researched and managed by other professionals outside of an «urban» context, so they are very rarely incorporated into spatial plans, thus leading to the disconnectedness and weakness of planning documentation which we mentioned earlier.

Revival of discussion and critical evaluation on the city level with experts as well gives Kyiv the potential to become a city with both an overlay and integration of short-term and long-term projects, in turn leading to more and more human- and nature-oriented solutions, grounded in real context, as shown in the diagram below.

A suggestion instead of a conclusion

The era of post-socialist technocracy is over, but in Kyiv, the era of new critical institutions and public engagement has clearly not yet fully emerged. We firmly believe that the existing urban planning system is broken and outdated. It lacks credibility in the eyes of active citizens, politicians, and businesses. And as we have argued, the worst of the current planning system’s provisions have led to unsustainable development, while the best have been easily bypassed by ill-intentioned speculative developers. In a practical sense, it is necessary to abandon the futile attempts to modernize or legalize the project of the General Plan 2040. But to change the system, we need to have courage and time to reconsider the basics, and to answer thoughtfully and publicly the questions often left aside, such as: How does planning strategy interact with the forces of democracy? For whom is the city planned? What is the role of planning in urban development? How can an average citizen help the city to become a better place? And what does a «better place» really mean?

Thinking back to our ancient Cypriot city of Khirokitia, we can recall that for hundreds of years, urban dwellers strived for a balanced city and that more often than not they were able to negotiate different interests with the view of the common good in mind. Surely, the complexity and speed of the current city life is no comparison to earlier ages, but there do remain many, many underutilized opportunities for people to take part in the creation and management of the city. Kyiv is a city ready for citizen-driven planning.

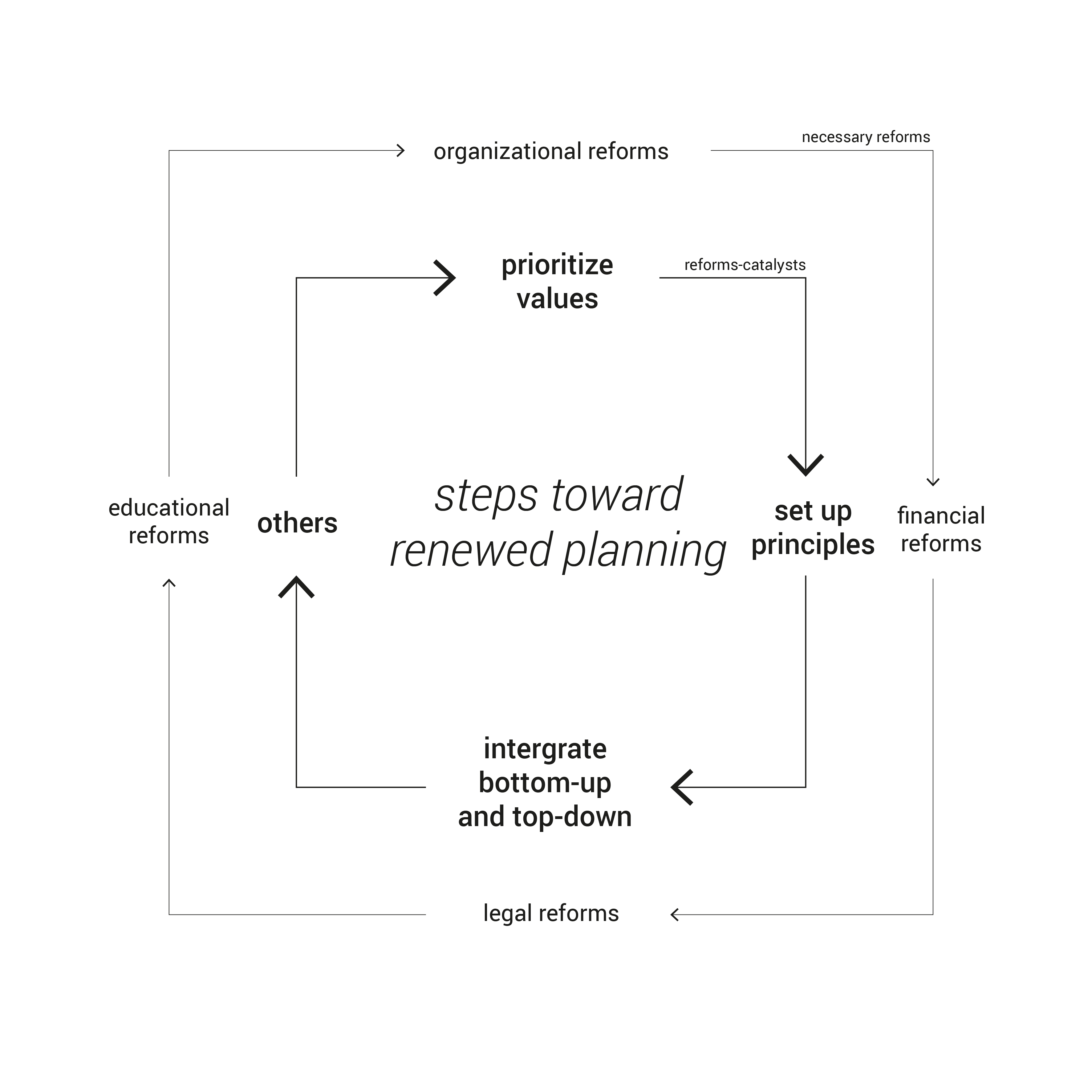

We are confident that shifts in the planning paradigm, such as those that we have suggested in our three-part article, have to come before changes can be made to the legal aspects of city planning and management. The city administration can no longer play a secondary role, not during an era in which speculative market forces are overriding the existing legislation and establishing a parallel world to the general planning system, leading to the disastrous mobility, energy, and land use situation that we have described in our articles. The current system’s seemingly mythical faith in quantitative and precise planning documentation cannot compensate for the insufficient competence, non-involvement, and lack of leadership shown in the actual administration of this system.

Today, the personal responsibility and positioning of Kyiv planners are very blurred, and their role and responsibilities are both distanced from the real changes happening in the city and disrespectful of the actual desires of the majority of Kyiv citizens. Only through embracing new, flexible, citizen-centered paradigms, shown in the diagram below, can we, the Kyiv society, begin the process of reinstalling public trust in the planning profession and restoring the profession’s ability to provide public goods to citizens in a transparent and democratic way. These restorations will permit the subsequent transformation of practices and rules to take place. The authors hope that the next generation of urban planners, by reflecting on the values and principles outlined above, will be able to critically engage in the process of creating new planning for Kyiv, and in abolishing the current system that compromises planning ideals in favor of short-sighted decisions.

- Oleksandr Anisimov, researcher at Bureau online, MS student 4Cities Urban Studies program (University of Vienna), go.oleksandr.anisimov@gmail.com.

- Anastasiya Ponomaryova, fellow in Advanced Urbanism and Urban Studies and Planning (MIT), MS in Urban planning (KNUCA), Urban Curators, shtnastya@gmail.com.

- Brent D Ryan, Ph.D., MArch, Associate Professor of Urban Design and Public Policy and Head, City Design and Development Group, Department of Urban Studies and Planning (MIT).

References

Burckhardt, L. (2019). Who Plans the Planning?: Architecture, Politics, and Mankind. Birkhäuser.

Blesser, B., & Salter, L. (2007). Spaces Speak, are You Listening?: Experiencing Aural Architecture. MIT Press.

Campo, D. (2013). The accidental playground: Brooklyn waterfront narratives of the undesigned and unplanned. Fordham Univ. Press.

De Certeau, M. (2011). The Practice of Everyday Life (3rd ed.). University of California Press.

Forester, J. (1982): Planning in the Face of Power, Journal of the American Planning Association, 48:1, 67-80 DOI: 10.1080/01944368208976167

Habraken, N. J. (2000). The structure of the ordinary: form and control in the built environment. MIT press.

Hall, P. (2014). Cities of tomorrow: An intellectual history of urban planning and design since 1880. John Wiley & Sons.

Harvey, D. (1989). From managerialism to entrepreneurialism: the transformation in urban governance in late capitalism. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 71(1), 3-17.

Hew T. (Ed.). (2017). Values and planning. Routledge.

Jacobs, J. (2016). The death and life of great American cities. New York, Vintage Books.

Lefebvre, H., & Nicholson-Smith, D. (1991). The production of space (Vol. 142). Blackwell: Oxford.

Lydon, M., Bartman, D., Woudstra, R., & Khawarzad, A. (2010). Tactical Urbanism (vol. 1). Recuperado el., 15.

Marcuse, P.(1976) Professional Ethics and Beyond: Values in Planning, Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 42:3, 264-274, DOI: 10.1080/01944367608977729

Ryan, B. D. (2017). The largest art: A measured manifesto for a plural urbanism. MIT Press.

Schön, D. (1938). The reflective practitioner. New York, 1083.

Southworth, M. F. (1967). The sonic environment of cities (Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology).