In this article, we assess and critique the foundational principles behind the creation of the city of Kyiv's key and sole formal planning instrument: its General Plan, proposed for passing and released on the 3rd of March 2020. We contrast the new Plan's approach to urban development with alternative, contemporary aims and principles outlined in the New Urban Agenda (NUA), the Leipzig Charta, and the Kyiv City Strategy.

The assessment shows the negative repercussions and inconsistencies of the new Plan. As we discuss and debunk critical principles of the General Plan, we argue, in turn, that Kyiv needs to foundationally and immediately rethink the values, aims, and power relations within its decision-making process for urban planning and development. Off-the-shelf, obsolete planning solutions to tactical-level issues should be abandoned, and a revised, participatory, democratic, and pluralistic participation process should be enacted instead. Only at that point will Kyiv be ready to create a master plan that genuinely offers innovative and broadly-supported ideas for needed improvements.

Where it all started

Eighty centuries have passed since the inhabitants of Khirokitia, in what is today known as Cyprus, created the first known «urban» street. Citizens of Khirokitia collectively agreed upon, built, and maintained their city's central street on their own. This collectively designed street was not merely a space between the buildings, but a space for communication, trade, and mobility (Lydon & Garcia, 2015). While this ancient Cypriot precedent may seem distant from contemporary urban planning conditions in which computers, engineers, and politicians seem to shape the city, the example of Khirokitia testifies to the power of horizontal, citizen-driven initiative, and to the basic fundamental human desire (Lefebvre & Nicholson-Smith, 1991) to participate in shaping the city. Khirokitia speaks to the social value of city spaces, and the essentially social process of city design.

As the population of cities grew in the post-medieval period and as political systems changed to permit a stronger, sometimes authoritarian state, citizens' influence in shaping the process and form of cities diminished. In some cases, citizen wishes became subsumed to a hierarchical, top-down system, disappearing entirely in the most extreme cases. First, the enlightenment then the twentieth-century Modern movement, pioneered the use of a rational mind, the application of planning and industrial technology, all while fostering the creation of ideal cities and elevating the role of a planner-architect-engineer (Ryan, 2017; Mumford, 1961; Sennett, 1996). The ancient, vernacular, collective practice of shaping the city environment was abandoned as professionals and politicians took charge of urban futures. Today, this professionalized, politicized, mechanized reality of city building remains routine throughout much of the world. Citizens are mostly alienated from city planning. Kyiv, Ukraine's capital, is no exception.

After centuries of imperialist centralized city planning and development, Kyiv was presented in the 1990s and the first decade of the 2000s with the opportunity to regain a citizen-oriented and integrated approach to general planning. Sadly, this opportunity was missed. Ukraine entered a confusing era in which neither the admittedly hierarchical yet rational Socialist planning model, nor the vernacular, citizen-driven historical planning model, were followed. Instead, a haphazard era of privatized planning in the 1990s and 2000s led to a mixture of state, municipal, and private companies controlling the planning process. This efficiently eliminated expertise and critical discourse in favor of short-term profiteering and rent-seeking.

In today's Kyiv, decisions about the disposition, utilization, and development of urban space are made behind closed doors, to the benefit of specific business interests, and with minimal participation of citizens. (Verbytskyi et al., 2017, Cybriwsky, 2016) Still, citizens suffer the consequences of poor and absent planning: the car parked on the pavement, the smog filling the air, the lack of safety in public spaces. But this suffering public, little informed about its rights to participate in planning, struggles to grasp the connection between the poor-quality urban realm, and the flawed decision-making process that shapes urban planning in Kyiv today. As a result, citizens are unable to influence these processes. While there are more and more signs of an «insurgent polis» (Swyngedouw, 2007) manifested in transgressive events such as clashes with developers and protests, such events in Kyiv are rarely linked to the biased, corrupted decision-making process of urban planning that continues to operate without restraint at the city-scale.

The recent so-called «public debate» of the Kyiv General Plan 2040 (Kyivgenplan, 2020) released on 3rd of March 2020, demonstrates the wide divergence of views between the city's rightfully mistrustful citizens, divided professionals, and seemingly impervious public authorities.

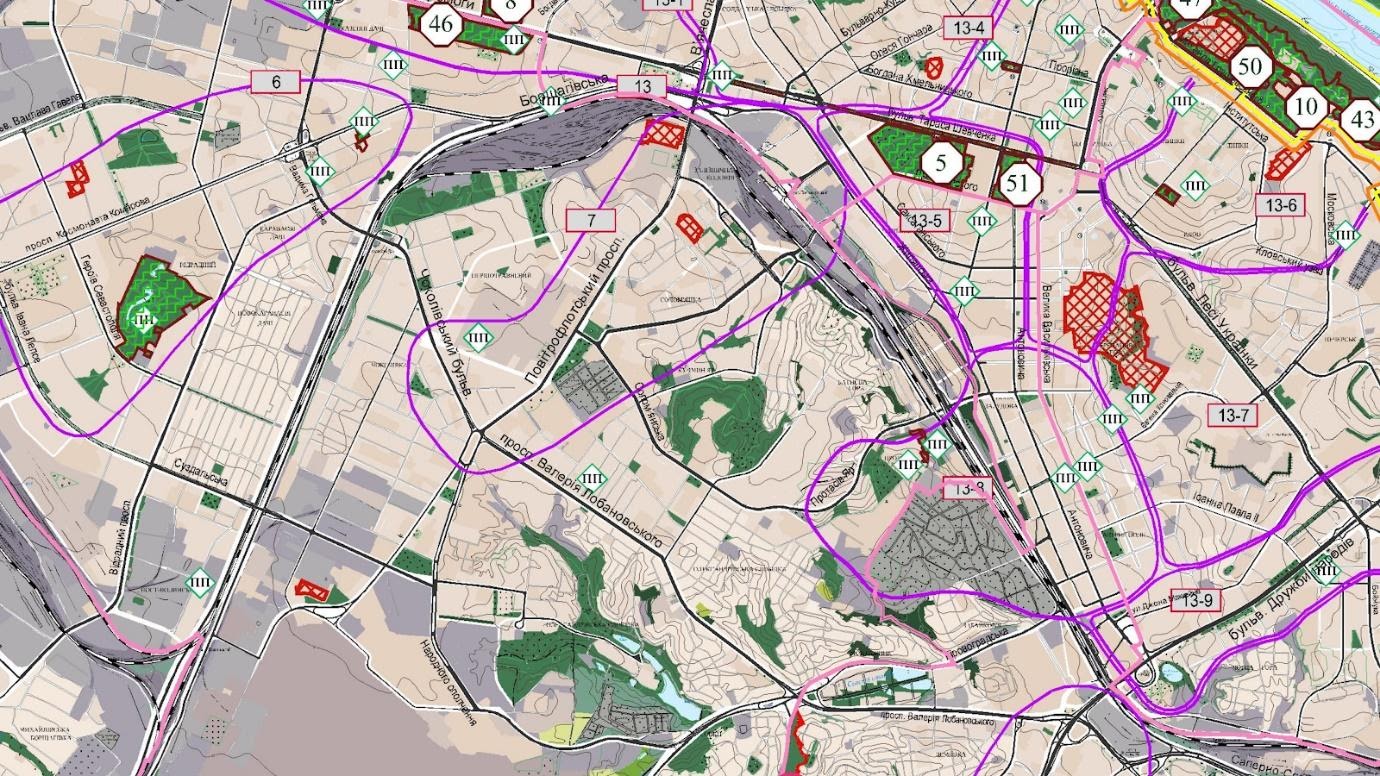

It is important to note that GP is illegible for citizens and is hard to read and understand even for professionals. The visual representation of schemes and its terminology is confusing. Readers are puzzled by the range of colors in a palette, whereby similar colors correspond to the entirely different functional uses. E.g., detached houses and beaches are both shown as acid green [ed. the image is available on the official Kyivgenplan website, slide 6 ]. The GP 2040 also includes many professional terms without providing definitions — e.g., city road, regional road, preservation areas, meadow park. The GP authors suppose that citizens will find definitions of the construction norms by themselves.

Still, planners expect a formal «public debate» to be conducted successfully. Active citizens demonstrated distrust of the official «public debate» that started online in April 2020 by launching an alternative platform for the discussion among citizens. This was named «Genplan for Kyivans» (Генплан для Киян).

While the current online discussion among citizens and experts revolves around specific parts of the general Plan, we do not wish to make a comprehensive analysis of every proposed action. The scope of this paper allows us to bring three of the most urgent problems to the foreground of discussion and what is more important to reflect on the underlying principles of present-day planning in Kyiv. We aim to contribute to the professional debate on GP 2040 by raising needed questions about values, vested interests, and long-term aims, rather than specific solutions. Therefore, we divide the article into three sections:

- Throughout the first article, we examine aspects of public space, ecology, and integrated planning of the General Plan of Kyiv 2040 to show the critical consequences that will arise if this document is approved in the city council.

- Secondly, we dive into the problems and shortcomings of the decision-making process, values, and principles lying behind the creation of the GP. (Part II) Thirdly, we open up a discussion about the potential ways to create a new design process in urban planning. We do not intend to create another ideal General Plan, but we argue for an urgent need to reform the whole planning process.

- Finally, «getting back to Khirokitia» would mean decentralizing decision-making in planning, empowering communities (hromadas) to take responsibility for the local affairs, and putting people in the center of the main processes of city management.

Part I. A Plan that gives us the past, not the future

Although master plans are supposed to be comprehensive and acknowledged as being all aware, the new General Plan of Kyiv fails to deal with the contemporary urban situation. Instead, it recommends strategies that were current in the past, not prepared for the future. The Plan is outdated in three respects: it denies the validity and importance of public space, it promotes unsustainable rather than sustainable thinking, and it exacerbates the disconnected nature of local spatial plans.

Kyiv's Infinite growth Paradigm: How the General Plan ignores life after climate change

Kyiv ranks as one of the least liveable cities in the world, according to the EIU index (117/140) and Mercer ranking (173/221). The capital of Ukraine is very far from having the kind of quality of life and environmental actions achieved by central and western European cities like Vienna, Berlin, or even Warsaw. Achieving higher environmental performance is an urgent matter in a world threatened by the global climate crisis. Loss of arable lands, worsening water, and air pollution, and increased contamination by plastics are just some of the many environmental problems affecting city administrations around the world. New urban policies to address these problems are urgent, and urban planning and design can play an important role, providing adaptive, responsive strategies such as traffic calming, green buildings, and energy transitions. Yet a progressive attitude to environmental challenges is absent from the new Kyiv general plan.

The Kyiv of the future will be obliged to use its natural resources — air, water, energy — more wisely, not only because world standards require it, but because of the national security, public health, and economic well-being of Ukraine and Kyiv will depend upon increased environmental responsibility. Enhancing a city's ecological performance should be a central, perhaps The central, aspect of any urban plan. Yet our reading of the city's new General Plan revealed several shortcomings and absences in the area of environmental responsibility. First, we found that the very terms that are widely used in contemporary sustainable planning are absent from the Plan. Second, we found an absence of planning tools that are considered as best practices by contemporary global organizations. And lastly, we found that the current Plan remains reliant on traditional planning methods that increase, rather than decrease, unsustainable, and environmentally irresponsible planning.

The absence of sustainable and environmental terminology. Although there are references to the Leipzig Charta scattered throughout the document, reading through the proposed numbers and spatial solutions, it is hard to trace these policies` influence on the document. Discourse-wise, «development,» «construction,» and «growth» are mentioned in the text 278, 249, and 35 times respectively, conveying a friendly attitude to builders. Environmentalists receive little respect in the Plan. However: «sustainability,» «resilience,» and «climate change» are mentioned 21, 0, and 1 time respectively. Even more important is the fact that none of these terms are explained in their relation to Kyiv's context and future. The Plan's lack of environmental consciousness is shocking.

Although every sphere enjoys at least a small analysis of the current condition, an environmental block is lacking even this. Conceptual framework of the interconnections between proposed measures — e.g., transport network construction, housing development, and their impact on the natural environment is absent. Thus, the solutions of this part are created on their own, uncoordinated, and isolated from all the other document proposals. We know well that integration of ecological measures in the core of all the spatial planning processes is the key to tackling the current challenges. Creating frameworks to build ecologically, to reduce the need for maintenance, to «unbuild» derelict structures and lands are all parts of a systemic understanding of the role of spatial planning in achieving sustainable ways of living in the city. We would like, therefore, to question the origin of the solutions in this section of GP. We note that the block of GP dealing with the protection of the natural environment does not provide us with any references of why, or how, these solutions would work. The current discourse can be summarized as «it is completely normal to build 20-story towers wherever and plant grass around to mitigate the effect».

The absence of contemporary global best practices. What one hopes to find, but does not t find in the document are any references of how Kyiv is going to tackle pressing problems like increasing air pollution, mitigating the heat island effect, preventing street flooding, or shortening food miles. None of these urgent ecological problems, all of which can be addressed by progressive planning, are analyzed in considerable depth. There are sadly no particular parts of the document dealing with urban resilience and reaction to global climate issues.

The General Plan lays out a proposal for further «development» in all directions: road infrastructure, bridges, engineering complexes, transport hubs, new residential, and office district development. This agenda is good news for those who wish to build, but the impacts of the proposed development on the city ecology are not evaluated. We are aware, however, that according to the current law of Strategic Ecological Assessment (On Environmental Impact Assessment, 2018, sec. 9), that an environmental analysis had to be made, and that a summary report had to be publicly discussed. This has not happened, at least not to the authors' knowledge. Though the Institute of the General Plan states that the environmental protection section of the Plan is itself a report, this seems like obvious cheating. The Environmental protection part does not contain required monitoring, evaluation of the impact of the proposed 'developmental' measures, nor an explanation of research limitations. Most importantly, the research results were never publicly discussed. The report is not only a fundamental instrument to restrict planners' ambitions, but also a possibility to compare the proposed goals and their realization to produce valuable findings for the future planning cycle.

On the very last page of the document at the end of the list of «action plan,» we found a few mentions of «sustainability» measures. None of them seriously tackles the problems of the increasing use of energy, car dependence, and in general, this section shows a further detachment from the measures outlined in other spheres. The introduction of non-renewable sources is, for some reason, linked to IBRD financing instead of the solutions through municipal legislation and land-use in GP 2040. The Energy Efficiency improvement program exists in the political and economic vacuum without any references to contemporary national and international programs already in place (State «Warm credits,» GIZ energy efficiency, IBRD projects). And mentioning the Kyoto protocol is absurd, as it has been 6 years since the Paris agreement and 4 years since Ukraine published its National contribution (REF).

Read more:

Post-Soviet Podil: industry transformation and architecture preservation

The Plan is reliant on outmoded and environmentally unsustainable planning ideas. While the aforementioned fundamental spatial responses to the environmental challenges are missing, some extensive solutions may be found in Chapters 9 and 12 of the Explanatory report. Among others, there are recommendations of increasing green space per inhabitant from 18,2 to 23,2 sq.m. per person within city areas and the creation of co-called buffer parks intended to prevent plant pollution. Both regulations are embedded within historic urban planning instruments for the socialistic city, which had distinct zones for work, leisure, and sleep and had its theoretical roots in the idea of the Garden City. Such logic does not provide analysis and regulation on the quality, diversity, and accessibility of green spaces. While certain districts enjoy a fair amount of green spaces, others have it privatized or obstructed by the road and railways. No coherent connections between existing and planned green spaces are outlined, limiting the possibility of walking, cycling, and animal movement.

There is no comprehensive answer to the problems of maintenance, which are, by now, equally important as the creation of new green spaces. Costly green areas that require constant watering and gardening are not a sustainable solution for the city. Low-maintenance parks, flood-resilient, and biodiverse landscapes such as wetlands are not projected by GP 2040 and, therefore, will not be created in the foreseeable future.

Summing it up, a lot of measures outlined in the GP 2040 will lead to harmful and unsustainable spatial development. The environmental protection block is weak and disregarded in other planning decisions presenting only a handful of the much-needed solutions to the contemporary challenges of climate change, resource scarcity, energy efficiency.

Disconnected Planning

Contemporary urban plans exist within a broad network of ideas, practices, and organizations. A range of international and national standards exist for elements of planning, such as transportation, public space, sustainability, urban design, and community building. Many of these planning ideas, standards, and practices are freely available, distributed online by nonprofit or professional organizations at low cost, to provide a reference point for plans being undertaken around the world.

Kyiv's new general Plan seems to have no connection to the contemporary world of widely distributed best practices in urban planning. Instead, the General Plan is intellectually isolated from planning standards, both local and global, such as New Urban Agenda, Charter of Public Space, or the Leipzig Charta. Nor does the General Plan take serious account of innovations in local planning practice. It does not build upon the existing Kyiv city strategy (PHC), Bicycle infrastructure development plan, the Integrated development plan of Podil administrative district. Instead, the General Plan seems connected to an older intellectual discourse: that of the urban norms that were released in Soviet times and were only slightly reformed in the two decades after Independence. Whilst the General Plan 2040 does barely mention integrated or sustainable development. It specifies every norm in construction and pledges that the principles of the City Strategy 2025, Leipzig Charta, and New Urbanism movement are taken into account. However, this stated commitment is dubious.

New Urban Agenda specifies that countries and cities commit to «Adopt sustainable, people-centered, age- and gender-responsive and integrated approaches to urban and territorial development by implementing policies, strategies, capacity development and actions at all levels by (...) Reinvigorating long-term and integrated urban and territorial planning and design to (...) deliver the positive outcomes of urbanization»; (New Urban Agenda, 2016)

Additionally, the Leipzig Charta stresses the need to «Make greater use of integrated urban development policy approaches,» by which the document means simultaneous and fair consideration of concerns and interests that are relevant to urban development. The Charta also states that «Integrated urban development policy is a process in which the spatial, sectoral and temporal aspects of key areas of urban policy are coordinated.«(Leipzig Charter on Sustainable European Cities, 2007)

The Kyiv City Strategy 2025 document, renewed by Kyiv administration in 2017, also puts forward several directions for planning, including "taking into account existing sectoral development concepts and European norms/standards in the field of sustainable urban planning and construction; "and "Implementation of the strategic environmental assessment procedure and other types of expertise and assessments provided for by European legislation in the development of the General Plan of Kyiv ". (Kyiv City Development Strategy until 2025, 2017)

Following these directives, we would expect that General Plan 2040 should pay attention to the sectoral city strategies in different spheres, such as the Bicycle Infrastructure Development Concept. The purpose of the Concept is to realize the objectives of the Kyiv Development Strategy until 2025 in the field of urban mobility. The aim is to reach a rate of 5% of daily commuting in the city by bicycle. Therefore, the main aim is to build no less than 24 km of the main cycle routes by 2023.» («The Concept of bicycle infrastructure development in Kyiv city,» 2017)

What we find in GP 2040 concerning this sectoral strategy does not support the statements mentioned above. The Legally-binding Bicycle infrastructure development Concept is not mentioned in the GP 2040 text, and its objectives are not integrated with the Plan either. Even more, for a hardly comprehensible reason, it is written in GP 2040 that a program for the bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure has to be developed in the future, despite the existence of such a development concept already.

When talking about hierarchical planning, there is another negative aspect of GP 2040. The expected binary General Plan — Detailed Plan planning was questioned in Kyiv in 2019. The integrated development concept of Podil administrative district (ISEK) was created as a specific, district-wide strategy. This formal but not legally-binding document was developed to mitigate the shortcomings of General plan 2020 on the local level and create guidelines for the district development according to the criteria of ecological, social, and economic sustainability. What could be even more important; it was based on about a dozen workshops and discussions with the locals and took the opinions of people quite seriously (fig.3). The GP does not mention this document or the importance for the other districts to develop such a strategy. Moreover, if the General Plan is agreed upon by the city council, it will block the realization of ISEK, as the solutions laid out in General Plan are inconsistent with those of the Integrated development concept of Podil.

Such examples are countless, and we mentioned only the most outstanding ones. The General Plan, in its current form, is inadequate for the needs of a contemporary metropolis with a complicated policy framework and myriads of stakeholders. The GP 2040 does not reflect today's highly pluralist, participatory society, instead of relying on outmoded notions of hierarchical planning.

Misunderstanding the role and idea of public space

What is happening with the public spaces in Kyiv today? We can outline two contrasting tendencies. On the one hand, there is a privatization of open spaces ranging from streets and parks occupied by cars and street vendors to the private-public appropriations of embankments and transport hubs. (Dronova & Maruniak, 2020; Mezentsev & Mezentseva, 2011, 2017) On the other hand, there is an emerging practice of common transformations of the spaces by the citizens (fig 4). With this in mind, we examined GP 2040 ideas for public space protection and the democratization process of its use and transformation.

We found contradictions as in the explanation and usage of the term public/civic space in the General Plan. The notion of «public space» in GP 2040 is a sort of hybrid of a Soviet, authoritarian model and a private-friendly model. The interpretation of «public» and civic space relies on the predefined categories of functions, whether it be recreation, communication, cultural, sport, or transport hub (page 22 in the Explanatory report of GP 2040). The GP 2040 inherited the notion of public space from Soviet times and therefore treated it as a regulated open space. This does not necessarily mean accessible for all, nor having a diverse functional use.

Read more:

Kyiv: interaction between local authorities and civil society

Open space, as understood in the NUA. (page 12. Glossary). «...safe, inclusive, accessible, green and quality public spaces, including streets, sidewalks and cycling lanes, squares, waterfront areas, gardens, and parks, that are multifunctional areas for social interaction and inclusion, human health and well-being, economic exchange and cultural expression and dialogue among a wide diversity of people and cultures, and that is designed and managed to ensure human development and build peaceful, inclusive and participatory societies, as well as to promote living together, connectivity and social inclusion.»

While the GP 2040 public space analysis fails to comply with any contemporary understandings of public space, «trade centers» are considered one of the key points of new «public» and civic spaces. Instead of engaging the city authorities in the development of new open and accessible facilities, authors of GP 2040 simply give away the city's primary responsibility to developers. (page 22 in the explanatory report of GP).

Most of the proposed open spaces in the city center cited by the GP for further development were, in fact, already planned in Soviet or even earlier, in imperial times: administrative squares, embankments, transport nodes, and religious squares. The Art Arsenal, the best-known national project of space transformation from industrial to public use, is a rare exception and is currently publicly inaccessible daily. Moreover, the list of «successful cases» in the GP is not supported by arguments regarding project quality. Most cited projects are comparatively insignificant: simple refurbishments of pocket parks or half-privately owned and monitored.

A future development plan of public spaces is, regrettably, not present in GP 2040. The document lacks any comprehensive understanding of its role in creating public spaces, e.g., in new residential/commercial development areas. The GP 2040 authors seemingly refuse to take responsibility for the quality and accessibility of public space in the city.

The only scheme distantly related to public spaces is the proposal for «The network of city centers,» which is extremely abstract, considering the other General Plan's action maps. The suggested list of old and new centers in the legend is difficult to trace on the map. Nor does the explanatory report help, as it does not provide a comprehensive definition and fails to draw a coherent picture of the city center listed for future development.

In summary, GP 2040 both fails to propose a new network of city spaces that is in any way comparable to the ambitiously realized projects of Soviet and imperial times, yet it also fails to understand the contemporary role of citizens and public life in activating urban spaces. The Plan lacks the ambition of the past but fails to incorporate the best lessons of the present, and it does not project substantial ideas for the future.

Part II will be soon published on Mistosite.

- Oleksandr Anisimov, researcher at Bureau nline, MS student 4Cities Urban Studies program (University of Vienna), go.oleksandr.anisimov@gmail.com.

- Anastasiya Ponomaryova, fellow in Advanced Urbanism and Urban Studies and Planning (MIT), MS in Urban planning (KNUCA), Urban Curators, shtnastya@gmail.com.

- Brent D Ryan, Ph.D., MArch, Associate Professor of Urban Design and Public Policy and Head, City Design and Development Group, Department of Urban Studies and Planning (MIT).

Bibliography

Cybriwsky, R. A. (2016). Kyiv, Ukraine: The city of domes and demons from the collapse of socialism to the mass uprising of 2013-2014. Amsterdam University Press.

Dronova, O., & Maruniak, E. (2020). Changing the symbolic language of the urban landscape: Post-socialist transformation in Kyiv. Handbook of The Changing World Language Map, 2941–2972.

Kyiv City Development Strategy until 2025. (2017). Executive Body of the Kyiv City Council (Kyiv City State Administration). https://dei.kyivcity.gov.ua/files/2018/1/11/Strategia.pdf

Kyivgenplan. (2020). General Plan of Kyiv 2040. Kyivgenplan. http://kyivgenplan.grad.gov.ua/

Lefebvre, H., & Nicholson-Smith, D. (1991a). The production of space (Vol. 142). Oxford Blackwell.

Leipzig Charter on sustainable European cities. (2007). 3. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/archive/themes/urban/leipzig_charter.pdf

Lydon, M., & Garcia, A. (2015). Inspirations and antecedents of tactical urbanism. In Tactical Urbanism (pp. 25–62). Springer.

Mezentsev, K., & Mezentseva, N. (2011). Kyiv's public spaces: Availability for population and modern transformation. 11(2), 39–47.

Mezentsev, K., & Mezentseva, N. (2017). Modern transformations of Kyiv public spaces: Prerequisites, manifestation and specifications. 22(1), 39–46.

Mumford, L. (1961). The city in history: Its origins, its transformations, and its prospects (Vol. 67). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

On Environmental Impact Assessment, Pub. L. No. № 2354-VIII (2018).

Ryan, B. D. (2017). The largest art: A measured manifesto for a plural urbanism. MIT Press.

Sennett, R. (1996). Flesh and stone: The body and the city in western civilization. WW Norton & Company.

Swyngedouw, E. (2007). The post-political city. BAVO (Ed.) Urban Politics Now: Re-Imagining Democracy in the Neo-Liberal City, 58–76. The Concept of bicycle infrastructure development in Kyiv city. (2017). In Концепція розвитку велосипедної інфраструктури в м. Києві. Kyiv city administration.

UN General Assembly. (2016). New urban agenda. Adopted at the United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III).

Verbytskyi, I., Hryschenko, M., & Pyrogova, D. (2017). Doslidzhennya mekhanismiv zalychennya hromads'kosti do proсesy pryinyattia rishen` kyivs'koyu mis'koyu vladoyu. In Research of the mechanisms of public participation in the decision-making process by Kyiv city administration. CEDOS. https://cedos.org.ua/uk/articles/mekhanizmy-uchasti-hromadian-u-protsesi-pryiniattia-rishen-u-kyievi-rezultaty-doslidzhennia