Efe Ogbeide is a co-founder of the FEMMA Planning studio in Helsinki, which combines urban planning, community engagement, participatory work, and creative practice in its projects. To talk about her experience and the complex context of Helsinki, Efe invited me to her home in a neighbourhood of East Helsinki known for its cultural diversity but still carrying the stigma of being “unsafe” or socially “problematic.” From the kitchen window of Efe’s flat, one can see the protected coastal forest which residents defended from destruction a few years ago. As we talk, two deer pass quietly between the housing blocks. The presence of people does not seem to scare them.

Could you tell me how FEMMA Planning was founded, and what personal or professional motivations led you and your colleague, Milla Kallio, to focus on collaborative planning?

FEMMA Planning was officially founded in 2019, but our story goes back much further. I met my colleague, Milla Kallio, at university around 2012 or 2013. We were both part of the student-led European Geography Association, which organised exchange programmes between different European countries. Later, we both joined Helsinki Think Company, a university programme that helps students turn academic ideas into practical projects or businesses. It was our first experience with entrepreneurship, something quite new for both of us. Although my team was eliminated early, it gave me valuable insights and confidence to see entrepreneurship as a possible path.

Around that time, in Finland, what I would call the third or maybe fourth wave of feminism started to gain more visibility. Discussions about intersectionality and diversity became stronger, moving beyond the earlier focus mainly on white women’s experiences. I was involved in some activist projects then, like Good Hair Day, an event about preserving and caring for Afro hair. When I was growing up, hairdressers here didn’t know how to treat my hair, and it always looked horrible. I was also involved in the Feminist Forum. Those experiences shaped my interest in feminist issues and how they connect to urban space.

Through readings—Judith Butler and others who write about space and identity—I started to realise that urban planning often operates from a very narrow norm: it assumes an able-bodied, middle-class, ethnically Finnish user. The “default citizen,” in a sense. That realisation made me question how planning could better reflect different lived experiences—how people actually use and experience space differently.

Milla and I reconnected at a European Geography Association conference in Seville, Spain, on feminist geography, where we realised our shared interests. Back in Helsinki, we organised a peer-led open course on feminist urban planning, a topic barely discussed in Finland then.

I wrote my master’s thesis on how adolescents in Vuosaari experience their neighbourhood. The City of Helsinki invited me to present it, and a few years later, they commissioned us to do a small ethnographic study, which became our first project—and by 2019, we officially founded FEMMA Planning.

What is the main focus of FEMMA Planning? Could you share something about the projects that best represent FEMMA’s way of working with communities?

In the beginning, FEMMA Planning did more projects that focused on specific groups—for example, the project with teenagers who have disabilities. We explored how they experience urban space. But over time, we began to feel that such projects were not quite the right format for us. Working with vulnerable groups requires long-term commitment and continuity—people who can build stable connections and return year after year. That is something we do not have the capacity to provide unless there is already an existing association involved, like an organisation that works with youth, or people struggling with addiction, or similar groups. In those cases, we can collaborate because there is already a sustainable structure. But as an external actor, stepping in for a short time and then leaving, it started to feel problematic.

Now our focus is more on designing participatory processes in strategic planning. These can happen on many different levels—regional, municipal, or local—for instance, when a city or community wants to develop a specific area.

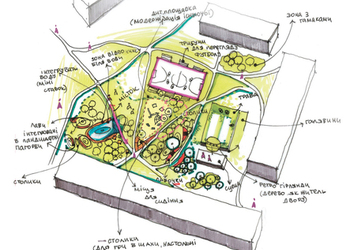

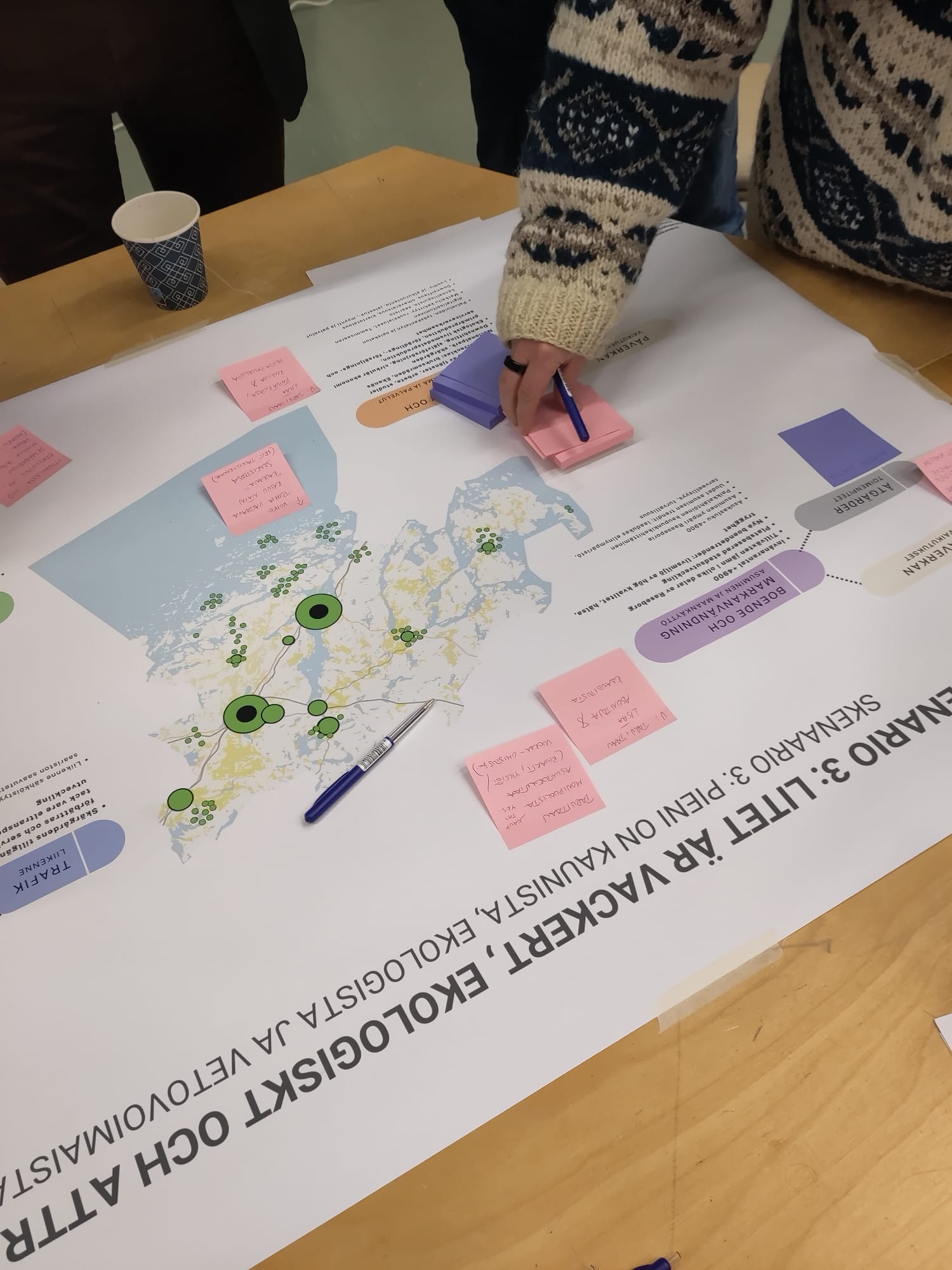

One example is our collaboration with the City of Raseborg, on the west coast of Finland, about a hundred kilometres from Helsinki. After several municipalities merged, the city faced challenges in uniting areas with very different identities—coastal, rural, and urban, some with train connections and resources, others without. The city architect Johanna Backas wanted to create a flexible land-use vision first rather than a legally binding master plan, something that could inspire shared direction. We organised workshops in each village to discuss how residents imagined their future while addressing real issues like population decline or climate change. Based on these discussions, four future scenarios were developed—from a fully decentralised, sprawled structure to highly centralised models—and we facilitated dialogue among city departments and politicians to evaluate them. Through this process, people realised that maintaining full services everywhere was unsustainable, leading to a consensus around focusing development on three main centres and existing infrastructure, while smaller villages would keep distinct cultural or heritage roles. The vision was ultimately approved by the city council—a historic step after years of failed attempts—and we continue to collaborate with Raseborg as they move toward the official master plan.

How do you consider intersectionality—e.g. overlapping identities like ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status—in your participatory design work?

I can share another example here, which is a project made in collaboration with an association called Seurasauna—it roughly translates to “Sauna for All,” or “More Accessible Sauna.” In Finland, we have public saunas that are often described as part of our cultural heritage. The common narrative is that they are open to everyone: they are affordable, you can buy a ticket and go, and there are usually separate sections for men and women, or sometimes mixed saunas where you wear swimsuits, or sometimes you are naked. These are quite an essential part of Finnish culture.

You can sometimes swim at the same time, and it is considered a nice, collective way to meet people and also to relax—there is a wellbeing aspect to it. The common belief is that saunas are sacred places, very Finnish, and that everyone is welcome, that there are no issues because everyone is equal there. But, of course, that is not really the case. These spaces are often very binary. If you do not identify as a man or a woman, or if you are transgender, it can be difficult to go to the sauna. Many Muslim women do not feel welcome, and people of colour often experience racism in those spaces. For people with disabilities, it can be physically difficult to even enter.

The sauna association had already been thinking about these issues and wanted to work with us. So we started to discuss how we could explore them further. We applied for funding and began organising “sauna workshops” with different groups. We collaborated with Trasek ry, a human rights organisation for trans people; with the Kynnys ry association for people with disabilities; and with another organisation, Amal ry, promoting the well-being of Muslim women.

Through these collaborations, we identified many issues. We continued working with the same participants, visiting public saunas together and discussing how to improve their experiences. These conversations later resulted in a small publication.

One really interesting outcome was that many of the suggested solutions overlapped. For example, both some Muslim women and trans people expressed the need for more privacy. People wanted to have more private spaces because others were staring or making comments about their bodies. Many of the solutions were quite simple—like installing shower curtains, having curtains in the changing rooms, or allowing people to cover themselves with a towel or wear something light. What we also noticed during those sauna visits was that many of the problems had deeper social roots. For instance, maybe it would not be a problem if the norms were simply more open.

At first, we assumed that Muslim women did not want to be naked because of religion, but when we worked with a group of Somali women, they said, “No, it is not about religion. I just have a bad body image. I do not like my body. I do not want to show it.” So it was actually the same reason many other people might have. And interestingly, when we created a safe space and went to the sauna together, in the end, they wanted to be naked—it was no longer an issue. That was an important realisation: that in Finland, there are still very stereotypical ideas about immigrants or certain groups, and we often fail to see personal experiences and struggles behind them.

It also showed us how much everything depends on the conditions—on creating a sense of safety. Even if someone has certain religious or cultural limitations, if they feel comfortable and respected, the experience can be completely different.

There is ongoing discussion about spatial and social segregation in Helsinki, with differences growing between neighbourhoods in terms of income levels, housing, and migrant population. Could you tell me more about the context and how the city is addressing it?

Even though Finland can be seen as quite homogeneous, it has in fact always been diverse—home to Tatars, Sámi people, Jews, Roma, Karelians, and many others. In terms of international migration, Helsinki has changed a lot over the past years. I was born here in the late 80s, and when I was growing up in the north of the city—in a rather wealthy suburb—it was quite white and homogeneous. I lived in public housing, but still, there were very few migrants at that time. Before the 1990s, the biggest migrant groups were small communities of the Vietnamese and Chileans who came because of the war in Vietnam or the Pinochet dictatorship. People like my father, who came in the 1970s to study, were not refugees but individual students.

Then in the 1990s, things started to shift. During the war in Somalia, many Somali refugees came to Finland, especially to this neighbourhood where I live now, in East Helsinki. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, more Russians and Estonians also arrived—these became the biggest groups.

Before that, Finland was still quite open in its immigration policies, at least compared to today. My father, for example, came to study here for free. But the early 1990s recession brought many changes. The economy crashed, many companies went bankrupt, and the government introduced austerity measures, cutting public services quite heavily. There were demonstrations, there was a high rate of suicide among people, families really suffered; I remember older people telling me how they had to reuse schoolbooks or cut rubbers to share.

Тут має бути галерея № 1

That crisis, to my mind, planted some of the seeds of today’s segregation. For example, the area of Meri-Rastila in East Helsinki was built in the early 1990s, just before the crash. When private developers could no longer continue construction, city and state-owned housing companies stepped in to finish the area. That is why much of the housing here is on rented land and is owned by the City of Helsinki, as well as by student housing associations that rent apartments to university students. Several social housing companies own buildings here. Many refugees were placed here and in other parts of East Helsinki.

But this is not the first time such dynamics have appeared. In the 1960s, when the city built large new neighbourhoods, they were first populated by people moving from rural areas within Finland—internal migration, not international. They faced similar challenges. Now the difference is that segregation also has a racial or ethnic dimension.

The reputation of neighbourhoods plays a big role. The price of housing depends not only on quality but also on what people believe about an area. You can find two almost identical housing areas in different parts of the city, but houses cost double because it has a “better” reputation and different demographics. Segregation does not necessarily correlate with the quality of services or infrastructure. Even areas next to the sea, with good schools, libraries, and a metro connection, can have a “bad” reputation. Actually, the metro is, for some people from more affluent backgrounds, almost seen as something negative—like a thing that brings “bad people” into their nice neighbourhoods. Some areas that used to be considered notorious have now been gentrified precisely because they have good services, proximity to the city, and strong public transport links.

In my opinion, another turning point came after the 2008 financial crisis. Before that, people mostly bought homes to live in. After the crash, this idea of housing as an investment started to take hold. People began buying extra apartments to rent out, and the housing market became more financialised—more about commodity than necessity. That has also deepened inequality.

You worked with neighbourhoods like Itäkeskus, which is known for its cultural diversity. Could you share more about these places, what kind of social or urban dynamics you encountered there, and the projects you were involved in?

We have done a few collaborations there, often connected with art institutions. One of them was in Itäkeskus, in the Puhos shopping centre. It was a place I had a personal connection to, because when I was younger, I used to live nearby. When it was built in the 1960s, it was considered an amazing, modern place—the first and the biggest shopping mall in Finland at that time. But later it declined, and by the time I was growing up, it had become rather shady—there were bars and it felt a bit unsafe, so my brother and I would always just cycle past it.

Later on, a lot of new facilities and shops run by immigrants from the Middle East and Somalia appeared—like prayer rooms, Alanya Market, Beno Market, halal butchers, and other places. It became a very vibrant and self-organised place, developed almost organically from the grassroots. Many of the entrepreneurs own their spaces. Because the prices were so low, they were able to buy or rent them.

Тут має бути галерея № 2

In 2019, we learned about an architectural competition that was being organised for that area. One of its main ideas was to demolish the shopping centre and build a new housing area there. We found that strange, because there had been no public discussion about it, and the place itself was so unique. It just felt like a very closed and top-down way of developing the area. It was a city initiative, of course—it owns the land—but still, it felt like a strange and non-transparent process.

At that time, participatory planning in Finland was not a new thing, but still less present in the public discourse. There was not much public debate about it. People could comment on plans or zoning decisions, but it was always more like the planners already had a clear idea, and the public could only react to it. So it was more about giving feedback than real participation.

We got some EU funding and decided to explore what the shopping mall actually meant to the people who used it. We did interviews, observations, and visits. We talked to shop owners, to people working in the area, and to a worker from a Helsinki city-run service for immigrants. What we found was that Puhos was much more than a shopping centre. It was a kind of social hub. Some people without papers would come there to find jobs or meet others.

The project was mainly about raising awareness and starting a discussion. We made a podcast episode and a small publication. It was not about proposing solutions—it was a small, research-based project. Still, it attracted some attention. Many people contacted us afterwards—artists and students, for instance—and a few bachelor’s and master’s theses were written about Puhos later on. I definitely feel it contributed to the public discussion about that place.

It was part of a wider conversation, too—about old shopping centres in Helsinki. Puhos is not the only one. There are several others, though not all are places where immigrant communities have created their own spaces. Interestingly, those that are like Puhos are often the ones under threat of demolition. Some that have been preserved are in wealthier areas and are considered examples of architectural heritage. So there is a clear inequality in how these spaces are valued.

When we speak about “participatory” urban planning, what does this approach look like in practice in Helsinki? The City of Helsinki has a participatory budgeting model. Could you tell me more about these tools?

The idea of the participatory budgeting model, Osallistuva budjetointi, originally came from Brazil. There, it emerged in the city of Porto Alegre and aimed to balance spending of public resources between richer and poorer neighbourhoods. It was rooted in a strong sense of social justice: how to distribute scarce resources in a fair and meaningful way.

In the Helsinki model, the emphasis on the social justice aspect is not so strong. Today, the city is divided into several areas—east, west, north, south, and central—and each receives a portion of the budget, probably proportional to population. Residents can propose ideas such as building a winter swimming spot, organising an anti-bullying campaign in schools, collecting drug needles in forests, installing benches, or transforming old buildings into community centres. The variety is wide: some initiatives are social, some recreational, and others concern things the city should normally take care of. People then vote on which ideas should receive funding.

However, in practice, when I look at the winning projects, they benefit the better-off areas within each district. I think results depend on which communities can mobilise voters most effectively. Of course, there are positive examples, at least from my middle-class perspective. For instance, we received funding for a public sauna here, which turned out to be a wonderful project—it brought a real sense of community. Our sauna received funding for around four years, after which support stopped. For us, it is still manageable, but it raises questions about continuity.

Another problem is participation itself: only around ten per cent—or even fewer—of Helsinki residents actually vote in these processes. I think that the Porto Alegre participatory budgeting has a stronger social justice component, as it specifically targeted those in need. When participation becomes “for everyone” without considering social differences, it tends to favour those who already have resources and agency.

Could you share more about the Dreaming Suburbs project and the context in which it appeared? You work in partnership with cultural institutions here.

It started quite organically and went through several phases. I first got to know Giovanna Esposito Yussif, artistic director of the Museum of Impossible Forms, which used to be based in Kontula—a neighbourhood often seen as lower-income, with a large immigrant population and fewer highly educated residents. Giovanna invited us to collaborate, and we did a short residency to explore what the important questions in Kontula were. Our aim was to understand how an art space like that could be more connected to the local community—to the people who actually live there.

Kontula is quite a stigmatised area. It is maybe not new information, but it is interesting: for many of us who live in places like Kontula or similar neighbourhoods, we love these neighbourhoods, we value them a lot. But for people who live outside, they are often seen as “ghettos” or areas full of problems. So the project was, in a way, about confronting this contradiction—the difference between internal and external perceptions.

Through Giovanna, we met Erik Annerborn from Konstfrämjandet in Sweden, Ulrika Flink from Konstfrämjandet Stockholm, and Lassen Iversen, who worked with Søren-Emil Schütt with the initiative Til Vægs in Denmark. Til Vægs is now a cultural space located in Lundtoftegade, a neighbourhood placed on Denmark’s so-called “ghetto list.” For example, if a neighbourhood has a certain percentage of residents from non-European countries, low education levels, and other such indicators, it can be added to the list, which allows for quite drastic measures like relocation. The people there fought back and were able to get off the list.

Together, we began visiting each other’s spaces in Finland, Sweden, and Denmark to learn from different contexts facing similar issues of segregation, neoliberalism, and displacement. From these exchanges, we developed the Dreaming Suburbs project, combining our background in urban planning with their artistic practices—creating an interdisciplinary project connecting art, activism, and planning.

When you begin a project, how do you design the participatory process?

It really depends on the context. In the beginning, we sometimes had pre-made modules or exercises, but we soon realised that every project is different. Of course, we still have certain exercises we often use—for instance, activities for people to get to know each other or ways to brainstorm ideas—but in general, we always adapt to the situation.

Working on Dreaming Suburbs and collaborating with MIF, Til Vægs, and others has taught me a lot about artistic research and artistic thinking. My background is in urban planning, where you identify a problem, map it, and look for solutions in a structured, time-bound way. Artistic methods are much more open and process-based, which has been new for me but very valuable.

When we work with municipalities on master plans, it is different—very structured, with strict deadlines and clear objectives. Then we organise workshops, round-table discussions, and similar formats.

What changes would you like to see in Helsinki’s urban planning practice (or in Finland) to make participatory planning more inclusive?

I think it is not really about the lack of knowledge; we already know what kinds of participatory methods or approaches exist. The issue is more about how to apply them, how to actually collaborate in an authentic way. Collaboration is often talked about as a nice idea, but in practice, I am not even sure what true collaboration really is. Often, it becomes: “Okay, we collaborate—you do this, I do that.” But how do you actually merge things from the beginning?

Another thing I feel, especially in the Helsinki context, is that the framework we are working within is quite problematic. What we are actually working toward is not well-being or some kind of planetary balance. The framework is still driven by growth and exploitation. I think that is something that really needs to change—it should be the basis that guides how we function and how we design things.

And then there is also the question of the framework itself, the conditions where we try to collaborate. It is difficult because everyone is so busy, expected to be so efficient. That is not a good foundation for collaboration. True collaboration requires time and space to develop new ways of working together, and that is rarely supported.

This publication is part of the Ukrainian Urban Forum 2025. The Forum is organised by the Cedos think tank, and the article was published with the support of the Heinrich Böll Foundation.