Doctor Julie Lawson is an adjunct professor at the Centre for Urban Research at RMIT University. With a background in public policy, particularly urban land policy, she has been conducting urban and housing research for 30 years. Julie was also the lead author of the Housing2030 report, which discusses the best policies for affordable housing across the UNECE region.

In May 2022, three months into Russia's war of aggression against Ukraine, Julie approached me via email, having read some of the housing-related publications I authored for Cedos. We had a short call discussing the deepening housing crisis in Ukraine and the growing need for an alternative to market instruments of housing provision. Thus began a long conversation about the future of housing in Ukraine that I am happy to continue today. Since 2022, Julie has advocated for social housing in Ukraine on various platforms and occasions "as an expert in policy, and largely as a volunteer academic," as she describes herself. Today, she works closely with Ukrainian researchers and policy experts, such as Pavlo Fedoriv, and together, they advise the European Commission and the Government of Ukraine on housing reform efforts.

As I speak to Julie in December 2024, the war-induced housing crisis is ongoing in Ukraine. There is an overall decline in housing affordability, and as the recent data collected by Cedos indicates, at least 42% of respondents spend more than a third of their monthly income on housing. The war has also caused massive destruction and displacement, leading to a change in the housing tenure structure. Before February 2022, more than 90% of people in Ukraine owned their homes, but by 2024, the share of homeowners had declined to 79%, and the share of tenants had increased to 14%. In big cities, the share of tenants amounts to 23%. Therefore, more and more people in Ukraine have found themselves in precarious housing situations, struggling to find adequate and affordable homes. Moreover, thousands of people remain in collective sites, a temporary accommodation provided for the internally displaced. Collective sites usually serve as last resort accommodation. Without secure and affordable alternatives to the private rental sector, there is a risk of people, especially older or disabled persons, staying in collective sites for prolonged periods. Even though, as the works of Madden and Marcuse suggest, the housing crisis might never be entirely resolved, there is always hope for creating a human-centred system that could cater to diverse needs. Thus, I speak to Julie about ways to approach such a system and renew Ukrainian housing policy.

Julie, you know that Ukraine is undergoing a massive war-induced housing crisis today. Housing has been one of the key issues for internally displaced people as well as other social groups around Ukraine. And that is why we are currently searching for new approaches. What do you think the key housing policy objectives should be, and what strategies are necessary to pursue?

We need to understand where Ukraine wants to go in addressing the challenges of the past and dealing with the problems exacerbated by the war. Ukraine has an aspiration to decentralise and empower municipalities. There has also been an enormous growth in the strength of civil society. But, of course, decentralisation also needs to be supported by adequate multi-level governance, transferal of resources and capacities, and the authority to do things. Multi-level cooperation requires frameworks to help decentralisation be a success. Housing is one of the responsibilities that has been largely decentralised. Therefore, there will be a need for effective support, not just authority but resources and capacities.

The big issue is the housing system's capacity to deal with the massive shock it has experienced. One consequence has been the shift of people into the rental market. The rental market is largely comprised of unprofessional or, if you like, accidental landlords. The market itself is relatively unregulated in terms of standard contracts or rent setting, rent indexation, and security of tenure. The enforcement of good practice isn't happening. There is no inspection of standards. There is no advocate to ensure the voice of vulnerable tenants is heard and acted on. Consequently, there are some adverse market mechanisms going on that need to be addressed.

In terms of the housing finance and construction sector, there are real problems for consumers in purchasing dwellings and accessing affordable credit to buy them. There are also problems for producers in adequate development finance, which leads them to rely on consumer contributions. This strategy is risky in itself, and there are good, well-regulated construction quality pathways to producing good places to live.

The other issue is around the quality of existing housing. There are a lot of people who have to heat their energy-inefficient homes. That costs them a lot of money, which, in turn, can cause high costs for governments supporting them if they're in energy-related poverty. So preventing that by improving the quality of energy-efficient apartment buildings is important, keeping in mind that most dwellings were built before the 1990s. Most of the existing dwellings haven't been renovated since they were built.

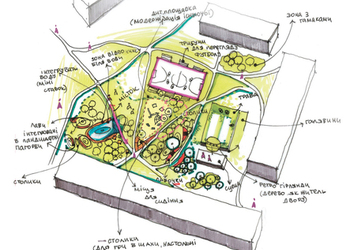

Another issue that needs resolution is around land policy and the use of planning instruments to ensure that municipalities are empowered to plan for a range of housing needs. European best practice would suggest that there are land policy instruments that local governments can and should use to ensure that they are meeting the changing needs of their communities. For example, in the way in which they acquire reorganised land, set use rights for that land, jointly develop that land or directly provide housing on that land. So there are roles and responsibilities involving land and urban planning that could be better utilised to cope with the needs and challenges in housing. There is a lot more proactive capacity that should be utilised to ensure that they can build back places that are well-integrated and of a good standard, that offer people a good quality of life, which is necessary, of course, to bring people back to Ukraine.

Any European best practice can only be an inspiration. It needs to be relevant to the institutional capacities and ambitions of the country. Otherwise, it will just be like water off a duck's back. And no matter how many times you say this model is the best one, it won't stick if there is no political interest in reform, if there is no middle-level and senior-level management in the public service which is curious and open to reform. If there is going to be any progress, it will have to be embraced by the public service and public servants involved in that process.

Let's also talk for a second about the rental sector, because in Ukraine, as you have mentioned, it's mainly comprised of private individuals renting their own apartments. There are few regulations, and they are rarely enforced. Recent data shows that housing is becoming unaffordable for a significant share of the population. Tenants are especially vulnerable. Moreover, vulnerabilities may compound. For instance, for older tenants, the situation is especially dire. You have mentioned such mechanisms as rent setting, rent indexation, and enforcement of standards. Can you tell me more about these instruments and how they work in other countries?

Rents can be set in different ways. There are three different ways you can run rent setting: market-based, cost-based or quality-based. First, they can be set according to what the market will bear. This means that if I come along and I try to rent a particular dwelling and another person comes along that can pay more, in a market setting, the person who pays more would be the one who rents the place, and the landlord would take the highest bidder, if you like. So market rent setting depends on market conditions — for example, how many people demand and supply to some degree. With the rent-setting basis that exists in Ukraine, millions of people currently want to solve their housing problem in the rental market, and very few people are offering housing for rent. Thus, in high-demand areas, rents go up a lot, while in others, they are relatively stable, perhaps even down.

In an ideal world with enough supplied housing for the demand, the rent level would be sufficiently affordable for the tenant and enough for the landlord to be interested in providing well-maintained, good-quality housing. But we know that, unfortunately, this is not the case. It is a market fantasy — in fact, particularly under wartime conditions, it's become a nightmare for tenants.

Therefore, other things can be done. It is better that we try to get to a situation where rents are reasonable and cover the cost of operating that dwelling well, maintaining it to a good standard, and covering the financing costs. We call that a reasonable rent cost recovery mechanism, where we enable rents to be set based on covering costs, covering maintenance, and covering some modest return but keeping those rents what we call reasonable. In circumstances where we don't have some kind of market equilibrium or an extremely low vacancy, that is one way of doing it.

Another way to set rents is on the basis of the quality of the dwelling. In the Netherlands, they use a point system based on the size of the dwelling and its quality; for instance, does it have good heating? Does it have a balcony? Does it have outdoor space? They work out the usable space of the dwelling and then its attributes and qualities, and they apply a point system.

Rents for low and middle-market dwellings are set according to that point system. If a landlord asks for more rent than the quality of the dwelling, the tenant can request a recalculation. There are rent commissions which assess if a landlord is asking too much for the quality of that dwelling. The system was brought into the Netherlands in the 1970s, and only recently its coverage has been extended to include most rental dwellings up to the middle market segment. The government is not concerned with regulating luxury housing but with the rents for housing targeted at the low and middle-income household segment.

Ukraine could decide, at little to no cost to the government budget, to go down a route which declares that rents should not increase arbitrarily since the beginning of hostilities in the war and can only increase, for instance, by an acceptable index, such as the cost of living or consumer price index (CPI). It means that rents may only increase in a modest, non-extreme way, because market forces in the housing market are particularly extreme.

In Germany, for example, they take an average rent for the area and create an index for each different market. That index would be the base rate, and then the increases or decreases allowed would be based on the consumer price index. And perhaps rent can increase or decrease only once per year, so that the change is predictable.

There is also the question of enforcement. The difficulty in the Ukrainian system is that we do have private landlords, and we do not know how many landlords there are or how many people are tenants. The particular challenge now is how to enforce the possible regulations in the sector.

Yeah, there are good examples in Europe as well. Again, in the Netherlands, you see that the enforcement role is increasingly becoming the responsibility of municipalities, which is appropriate because they are closest to the subject communities and are also responsible for planning the provision of housing needs. All landlords in the Netherlands must register with the local authority, the municipality. They also have to register the rental contract, what they are charging their tenants, the dwelling's size, and the amenities. They are also required to show a bank statement to demonstrate that the amount in the contract is actually what is being paid. That is a relatively new administrative requirement; it started last year. There is now a registry of landlords, if you like. If they do not comply with the point system that I talked about before, if they're setting excessive rents, they will be asked to change that. This opens up all kinds of room for better practice, also in terms of preventing bad practice.

One of the outcomes we saw was a wave of landlords selling their rental properties. But that's stopped now. There was a sort of shakeout of landlords that were not what we would call in the rental business “for the long haul”. Those who I would call more speculative rental investors have been shaken out of the market, which is a good thing.

Therefore, regulation can have a number of consequences. In this case, it has created more transparency over rent setting and better adherence to quality, which means you are getting value for money as a resident. It has also pushed out unprofessional landlords who shouldn't have been there in the beginning, creating a better culture of residential real estate.

Now, we've talked about one part of the equation — regulating the private sector. But let's also talk about another part — creating sustainable public housing. In Ukraine, there is now a discussion about social and affordable housing. Social and affordable housing is enshrined in the Ukraine Plan, which is the central guiding document for future reform. However, the questions of how the system should look like, how it should be financed, and who will provide housing are still open. Can you share ideas and thoughts on creating this sustainable public housing sector within the Ukrainian context?

It is probably a good idea to think about what you want social housing to be. Typically, social housing involves affordable housing and rental housing and is allocated to people on the basis of need. Rather than first come, first served, it's allocated in a purposeful way. That purpose is something that Ukraine can decide for itself.

Social housing can be provided on the basis of the particular objectives and priorities of each local community. For example, if it is a university town, it might have a priority to offer a good place for young students to live in the future, or it might have a priority to accommodate its elderly community. Another community might prioritise integrating new people coming from areas under occupation. Each locality needs to work out its own policy based on evidence as well as its own economic ambitions and make an evidence-based eligibility priority policy for what it wants social housing to be. A community might choose to focus on vulnerable groups, or it can choose to focus on a broader range of groups.

I hear some voices talk about not wanting to concentrate people who are really poor in one place or not wanting to create islands of very wealthy or very poor people. It seems, and the European Union would agree, that a more socially inclusive place probably has more potential for building stronger communities. Additionally, a broader range is better. We see that in countries that choose to have a broader-based social housing system, those systems are growing and becoming more resilient to change or political shifts. Such systems are also more supported by the general population.

For example, there is a broad-based “housing for all” social housing system in Denmark. In Austria, social housing accommodates most of the population. In Finland, you see a relatively broad approach as well, but Finland also prioritises emergency and high-needs cases. Those countries all have what I would call growing and resilient social housing sectors, which are broadly accepted and supported by their municipal and local governments. So they're genuinely places for people, for all people, and they are not socially stigmatised or excluded. I think we should look to those successful models and those growing models for Ukraine.

Another aspect is that social housing is owned and managed in different ways. There are models that favour municipal housing companies, non-profit associations, or rental co-operatives. However, you can find all three in those growing models. Interestingly, each of those social housing models is run on different bases.

The good ones that are growing also build up equity over time.

Social housing organisations that become economically strong and are able to grow and maintain stock well are typically run on a cost-recovery basis. They must balance their books every year, and often, they are run on cost-rent recovery. That means that the rent covers the operating costs, the financing costs, and the costs of maintaining the dwelling. Part of the rent goes towards a fund which would renovate the dwelling over time, perhaps making a new kitchen or a bathroom after 15 years. It keeps those buildings up to date and those homes well-maintained.

Of course, cost-rent of a high-quality building can be expensive. There are ways to bring those costs down. For instance, the upfront provision of land by the municipality. Secondly, by using conditional equity — for example, a grant or a soft loan, meaning a loan which is never repaid. These financial instruments would have conditions attached to them; for example, they would require those dwellings to be allocated on a cost-rent and needs basis. Additionally, they may require that all aspects of the construction be subject to competitive tendering. This way, the costs can be kept low so that the cost-rent is affordable for a typical teacher, nurse, or policeman. However, for someone on a pension or for someone who is a bit more wealthy, there's room within the rent-setting system to adjust those cost-rents. For example, you could set the rent higher for those with a higher income and lower for those with a very low income, and keep it at the cost-rent for middle-income households. This is a differentiated rent setting of the cost-rent. We call that cost-rent which is differentiated for the household, for the user. That is how you internally create more affordability within social housing.

Over time, providers also pay off the outstanding financing of the dwellings, thereby building up equity. The value of those buildings goes up if they are maintained well — that is how you grow social housing. That is how social housing grows in France. There are five million dwellings in France like this. In Denmark, interestingly, social housing even makes a return for communities. In a national fund, there is a dividend return that goes back to the government.

At the end of the day, social housing can be a very good investment for communities and governments to achieve not only good social housing and economic stability but also good energy-efficient, well-planned homes, which really is all part of building back better. So social housing is really what Ukraine will make it: either narrow, loss-making and welfare-only housing or cost-covering housing that is a good tool for social and economic development.

We have now covered costs and touched upon the management of social housing. We see that efficient, economically sustainable, and mission-oriented housing providers are at the centre of the system. However, how can we ensure that housing providers are doing their job right, that they maintain affordable and appropriate quality housing, and that they're not speculating? Are there any mechanisms that we can use to do that?

Yes, absolutely. There are some very simple mechanisms. One, set the rules right at the beginning. Any surpluses must be revolved around the organisation's mission. So you can have that in the new law, the social housing law. This is crucial to retaining and building up equity in that organisation in order to grow, maintain, and renovate over the years. Austrian law, Danish law, and Finnish law all require reinvestment. They have another important requirement: the equity cannot be extracted, and you can't simply sell off the dwellings for free or at a discounted rate. You cannot give them away because that is actually a kind of stealing from the equity of the provider, isn't it?

But that doesn't mean it's impossible to sell. Maybe there is a dwelling which nobody wants to live in; it is located in the wrong place and is not needed. Okay, well, you may choose to sell that one to buy a better one in the right place and location. If you must sell, then you can only sell it at the market replacement cost so that the receipts from the sale have to go back into the revolving fund to replace that dwelling in a better location or to suit the asset management strategy of the provider. Those kinds of rules are very, very powerful in protecting the assets of the provider and also ensuring that they continue to grow. You can see that in Austrian law very clearly.

There's been some work done by Austrian and Ukrainian researchers together to look at what it would take for such a law to be designed to suit Ukrainian conditions. And the European Union, through the New European Bauhaus, funded that research and produced a report called Housing for the Common Good. This report is a template for a model law based on Europe's probably most famous and well-regarded social housing system, the limited-profit housing association system in Vienna. It doesn't fit perfectly into the Ukrainian system, so it needs to be adapted and redrafted to suit.

It is bad practice when the requirements of social housing’s social obligations are only short-term. We see that in the dramatic impact it had on Germany. In Germany, there's no longer a requirement for continuity of those social obligations. And when they expire, the dwellings can be sold or reverted to a market basis of rent setting. At that moment, there can be a major loss of housing stock for social housing purposes. I saw in a 2017 study that Germany was losing around 100,000 units per year. That is why Germany has a very small proportion of social housing compared to all its neighbours. The big contrast is with Austria, where they’ve kept the good regulations, which is why the whole industry of limited-profit housing is growing and is a very important part of the economy today.

My last question for you today. Ukraine is also now experimenting with other instruments and ways to react to the growing housing needs. And one such instrument is a cash-for-rent program. The Ministry of Social Policy recently announced a pilot cash-for-rent program for internally displaced people. We know that cash-for-rent programs are sometimes used to quickly react to growing housing needs. However, we also know certain risks are associated with these programs. Based on your experience and international experience, what are the main shortcomings of such programs?

Demand-side assistance, which means assistance to help people pay, comes as rent assistance or rent allowance. Housing systems often need that kind of instrument for certain circumstances in people's lives. They might be pensioners on low incomes, or they might be ill for certain months or have a baby or whatever their circumstances, and they are unable to pay their full rent. Rent assistance helps them get through when they need to do so.

Those kinds of instruments are very useful when the rents that people are paying are also subject to some form of regulation. Because if we are assisting people to pay excessive or exploitative rents, then it's quite a waste of public resources, too. In the last 20 years, governments have shifted towards paying rent assistance in the private rental sector. But we have not seen rental sectors improve in terms of supply quality or tenure security. So we are pouring quite a lot of money into a sector which is not delivering quality outcomes. It is more effective if rent assistance is implemented in a well-regulated rental system.

I mentioned one method in the Netherlands where rents are set according to the quality of the dwelling. There are also other systems which only pay rent assistance to landlords that are committed to a certain quality standard, so that rent assistance doesn't just flow to bad landlords and enable them to keep being bad landlords.

Nevertheless, can rent assistance be more effective if it is combined on the supply side with good landlords and responsible landlords? If the only policy instrument is demand assistance or rent assistance and there is no regulation to effectively control the rent levels or the quality of the dwelling, then I would say it is a bit like pouring money into a bucket with a big hole. It does not affect any change in the supply of quality or quantity of adequate housing. The OECD, in its report called Brick by Brick, urges governments across the OECD region — including Ukraine, of course — to look carefully at the supply side and the mechanisms that can be used there to ensure more adequate and affordable housing.

Lastly, though, there's no doubt in my mind that rent assistance is a useful instrument for people on really low incomes. It's important to look at why they do not have enough income. Are pensions too low? Are jobs too insecure for people to rely on them for income? Are there other excessive costs in their household budgets, whether energy costs, childcare or other costs? We need to also look at the influence on the actual supply. At the end of the six months of the pilot, do people actually have improved choices to find in the market for themselves? Does it have an impact on supply, adequacy, and security of tenure? And if the answer is no, then relying on demand-side assistance is not the way to go. You have to address both the demand side and the supply side. It's a bit like driving with only two left wheels running. You need to have all four wheels on the road to go in the right direction.

At the end of the day, for Ukraine, the main thing is to understand what we want to achieve with the housing reform. And I would say that if the main goal is to ensure adequate housing for all and to react to the growing housing crisis, we do need political leadership, housing leadership, multi-level governance, diversity of instruments, we need to ensure that we have sustainable mission-oriented landlords, and also that housing is well-connected with other forms of social support and is part of a long-term strategy. That, in a way, is the essence of our conversation, and there is a diversity of instruments and best practices that have already been tested for decades in so many countries. We do not need to reinvent the wheel. We can test different instruments, adapt, localise, and see whether it suits the situation and our aspirations.

That was fantastic. I think you've said it in a nutshell and super well. It was a terrific conversation. Thank you for the conversation. Also, all thanks to the Ukrainian researchers who are out there, who are watching, researching, and asking good questions.

We prepared this interview with the support of the Housing Initiative for Eastern Europe (IWO e.V.) and the German Federal Foreign Office (Auswärtiges Amt, AA).